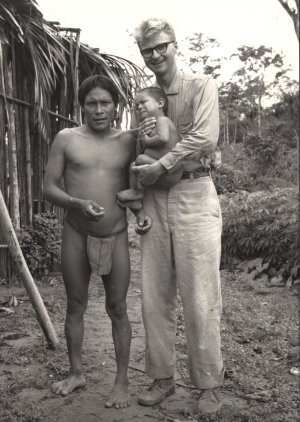

After venturing into the isolated Andes mountains of Colombia to reach the unreached Motilone tribe for Jesus, 19-year-old Bruce Olson was ambushed and shot in the leg with an arrow in 1961. His Yukpa guide fled as six warriors moved in and captured him, forcing him to stand and walk six miles to their tribal hut.

The Motilone indigenous peoples (they call themselves Bari) were feared by all outsiders because they killed anyone and everyone who made contact with them. Bruce says that such hostility stemmed from their fear that outsiders were cannibals, according his interview on the Strang Report podcast.

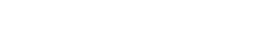

Bruce was allowed to recover, guarded in the hut. Three days after his capture, his first meal was a palm tree maggot, which he didn’t know how to eat. He was famished and when he cracked the exoskeleton with his teeth, the contents burst over his face and tasted like liquefied bacon and eggs.

Bruce was allowed to recover, guarded in the hut. Three days after his capture, his first meal was a palm tree maggot, which he didn’t know how to eat. He was famished and when he cracked the exoskeleton with his teeth, the contents burst over his face and tasted like liquefied bacon and eggs.

When he spotted bananas hanging in the upper supports of the communal hut, his eyes pleaded with his captors to be able to eat one, which they granted. He quickly learned the word for banana and would ask often for the tasty treat. On the third occasion that he asked for a banana, they brought him an ax instead, and that’s how he discovered their language is tonal.

“I felt as a young Christian convert in Minneapolis that my place would be among the unevangelized tribal people of South America,” he says. “I felt uniquely drawn to Colombia because I liked the literature of Colombia. I bought a one-way ticket to Colombia. After one year of learning Spanish, I ventured into the jungle to make contact with the Bari people.”

Eventually, the Motilone realized that Bruce was not a hostile threat but a human being just like them. He learned their language and learned to fish and live among these primitives. He was accepted by everyone except a certain fearsome warrior who could not reconcile with the idea of a friendly outsider and threatened to kill Bruce.

On one night, the mighty warrior came to take his life. But Bruce had fallen gravely ill with jaundiced eyes, and so the warrior desisted. Tribal superstitions forbade killing sickly persons.

Bruce — or Bruchko, as they called him — was essentially “civilization’s” first contact with the tribe that killed all previous Colombian emissaries, prospectors and oil explorers. He would travel into cities to buy medicines and supplies. On one such trip, he discovered a newly-invented flea collar for pets. He bought one — for himself — and wore it around his neck.

Success for his efforts came with the winning of a convert, who was just about to be initiated into manhood. The ritual included a contest of chanting lengthy poems among the men. It sounded eerily demonic to Bruce, who was uninitiated as yet to the custom, but as he listened intently, he heard his young convert tell about Jesus as all the others perked up to his tale.

It turns out the Motilone had the cultural belief they were separated from God, who lives beyond the horizon. They expected to re-find the trail to return to the horizon. It was a breakthrough.

Bruce took it upon himself to help bring education to the Motilones, sponsoring many youth to schools in the nearest city, Bucaramanga. Some have even become doctors, lawyers and agricultural engineers and returned to serve among their people. Christian doctrine taught the Motilone to care for the elderly and orphans, he says. He started a school teaching literacy.

He was heavily criticized by Swedish anthropologists who accused Olson of destroying the aboriginals’ culture. The secular anthropologists called for expelling Christian missionaries and linguists from under-developed regions of the world.

He was heavily criticized by Swedish anthropologists who accused Olson of destroying the aboriginals’ culture. The secular anthropologists called for expelling Christian missionaries and linguists from under-developed regions of the world.

“The gospel is not to destroy the culture that God entrusted to them, placing them in the jungle, but to bring redemption and deliverance,” Bruce counters. “We do not strive to destroy the culture of the people. We do not strive to show that we are superior.”

His book, Bruchko, is required reading in many seminaries, and John Allen Chau cited him as a source of inspiration in his fatal attempt to reach the remote Sentinelese in 2018. His ideas were and remain revolutionary in missiology. His approach to “going native” is still debated in seminaries. He is revered as a legendary missionary by some and held to be a loose cannon by others.

Bruce was kidnapped by the revolutionary National Liberation Army (ELN) in 1988 and summarily judged along the same lines of the arguments of the Swedish anthropologists. Condemned to die for “exploiting the Motilones,” he was ultimately freed two years later largely due to the published reports of journalist Maria Cristina Caballero, who interviewed countless indigenous leaders who advocated for his good work among them.

The president of Colombia later said Olson “is the first white man to be defended by the indigenous communities in our country, in Latin America.”

Today an estimated 70% of the Motilone tribe is Christian, thanks almost exclusively to the efforts of Bruce to sacrifice his life and give himself to the unreached. Granted Colombian citizenship in 1988, Bruce, now 80, is still alive and working with the people of 18 different tribes and languages of the jungles.

“The Motilone people are witnessing the resurrection of Jesus Christ to the neighboring tribes,” Bruce says.

“The Motilone people are witnessing the resurrection of Jesus Christ to the neighboring tribes,” Bruce says.

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

Michael Ashcraft also sells bamboo steamer baskets online for those who appreciate more natural cooking for vegetables and Chinese pork buns.

[…] Success for his efforts came with the winning of a convert, who was just about to be initiated into manhood. The ritual included a contest of chanting lengthy poems among the men. It sounded eerily demonic to Bruce, who was uninitiated as yet to the custom, but as he listened intently, he heard his young convert tell about Jesus as all the others perked up to his tale. Read the rest: Bruce Olson, Bruchko […]

Comments are closed.