By William Huan —

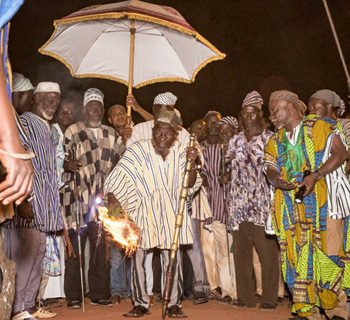

When I first saw the Fire Festival in Nalerigu, Ghana, it was an intense experience. My family had moved to the traditional seat of the Mamprusi kingdom only a few weeks earlier, and everything was new and exciting for us. On this particular night, a mob of men holding bundles of thatch gathered in the dark outside of the Paramount Chief’s palace. The king emerged in a processional surrounded by his royal court. Dozens of drummers followed behind beating drums and singing his praises. The king’s warriors completed the entourage holding their guns up high in the air.

He stopped, and a hush fell over the crowd. The king held up a burning torch, waved it around and threw it on the ground. The crowd erupted into cheers and the men rushed forward to light their own torches from its flames. The warriors lined up and fired their guns into the air.

The king returned to the palace, but the town was now in a joyful frenzy. Young men ran around waving and throwing their grass torches, guns continued to go off, boys tossed firecrackers in the streets, and everyone smiled and greeted one other.

With the help of our Mampruli language teacher and some friends in the community, we learned the story behind the Bugum Toobu festival (literally “fire throwing”).

Many years ago, the king’s son was out playing with his friends. He became tired and lay down under a tree to rest. The tree had a bad spirit that bewitched him into a deep sleep, and his playmates forgot about him and returned home.

That night the king and the queen realized their child was missing when they called him to go to bed. Distraught, the king ordered his people to go around the village looking for the missing son. They gathered thatch and lit grass torches to carry in their search.

When they came to the outskirts of the village, they found him under the tree in a deep sleep. They woke the boy and then threw their torches at the base of the wicked tree to destroy it.

The king’s warriors then gathered at the palace and fired their guns into the air to call the whole community to come and rejoice with the king. He decreed that every year, all the villages in his kingdom are to gather to remember this happy day and celebrate, for his son was lost but now is found.

Everyone Has a Story

In our international missions studies, my wife and I learned the importance of discovering bridges, or elements in a people’s culture that are compatible with the gospel. Missiologists call them bridge stories. Such stories affirm the stories, values or beliefs in a people’s culture and help them identify with a Bible story.

When we heard the story behind the Fire Festival, we immediately thought of the three stories Jesus told in Luke 15 of lost things that were found. We couldn’t have made up a better story that parallels the intense love of the King of Kings for lost individuals, and the joy of celebration in the heavenly kingdom upon their return.

Over the next year, we continued to improve our language skills and learned how to tell the traditional Fire Festival story as well as the parable of the lost sheep (Luke 15:3–7) in Mampruli. The next October when the festival approached, we shared the two stories with our friends in the community.

“Jesus’s stories allow us to build a bridge to the gospel and relate the truth that God is seeking out the lost and calling them to himself.”

The response we received was incredible. People were amazed that we knew their ancestors’ story and even more so that we could tell it in their heart language. Some excitedly called others over and had us repeat the tale to them. They said, “Sulimiiŋŋa wa mi ti kaari!” meaning, “This white foreigner knows our traditions!”

Time and again, this opened the door for us to also share stories from the Word of God. We recounted Jesus’s parable of the shepherd leaving the ninety-nine sheep to find the lost one and the celebration that ensued when the wandering sheep was found. Jesus’s stories allow us to build a bridge to the gospel and relate the truth that God is seeking out the lost and calling them to himself.

We Are All Bridge Builders

Although the Fire Festival is specific to my corner of the world, the stories in Scripture are not. Yes, they occurred in a specific time, place, and cultural context, but they reveal universal truths of God’s revelation to all mankind for all time. That means the Bible is relevant to your neighbor from a different generation, to your work colleague of a different race, to the immigrant you meet from a different country, and to the folks across town from a different social class.

As a follower of Christ, you are called to proclaim his glory among all peoples (Ps. 96:3). You have to be willing to put in the time learning and understanding God’s Word, as well as a culture that is not your own. You run a high risk of annoying, offending, or angering a new audience if you neglect to do your homework. Observe, listen, study, ask questions. Find out what makes a culture celebrate, mourn, and stir; then find a Bible story that connects with those catalysts. Be humble and patient, and these pursuits will grow in you a love for other people who might at first seem so different from you. God will open your eyes to ways you can build bridges from their stories to his story.

William Haun lives in northern Ghana in the heart of the ancient Mamprusi kingdom with his wife and their two children. He’s known locally as the “Sulimiinsina’akyinnaaba” or “young white men’s chief.” He loves learning Mamprusi proverbs, history, and folk tales and using those to communicate his faith effectively.

To learn more about the IMB, go here