By Mark Ellis —

Without the L.A. Crusade in 1949 – and the unusual promotion from William Randolph Hearst – Billy Graham may have never become the towering evangelist known to millions around the world.

“The 1949 revival was a real turning point in Billy Graham’s life,” says Neil J. Young, historian and author, currently a research scholar at George Mason University. “Had it not been for this particular revival we might not have had the Billy Graham we came to know.”

Graham seriously considered leaving the revival circuit before the L.A. event. “He was young, 30-years-old. He had been out on the revival circuit for a couple years but really felt he was not being very successful at it,” Young notes.

There had been a series of what Graham considered failed revival meetings. “He was seriously contemplating that being a traveling revival leader was not the work for him and what he was called to do.”

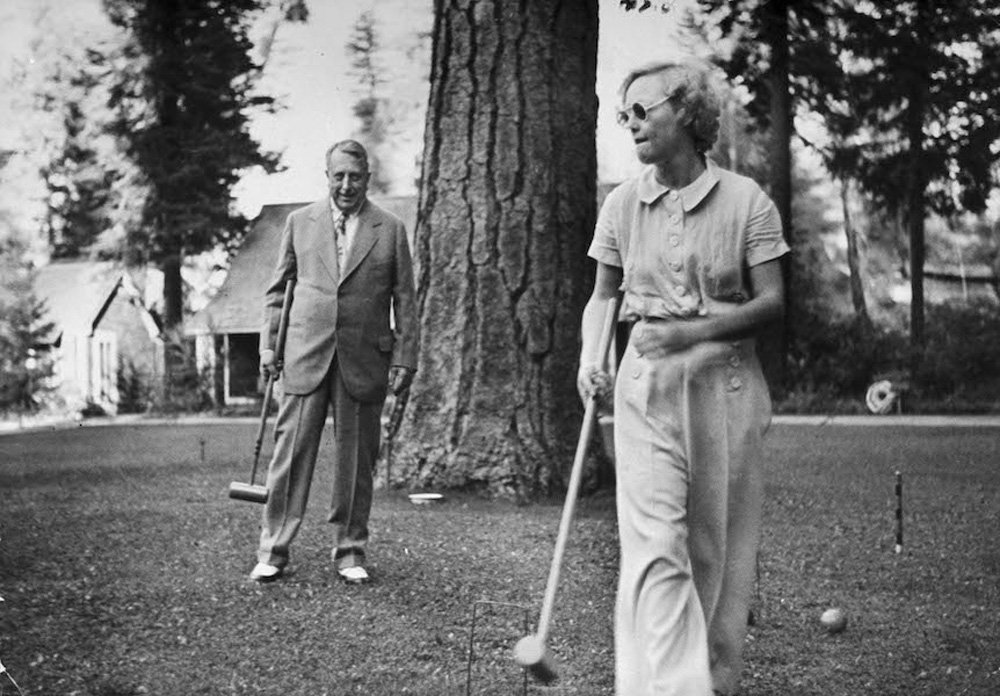

But then Graham went on a spiritual retreat at Forest Home in the San Bernardino Mountains for a time of prayer and contemplation – seeking God’s direction for his life.

“It was there (Forest Home) that he got the word that this was what he was supposed to do,” Young explains.

Shortly after leaving Forest Home, Graham was contacted by some Christian businessmen in L.A. that had tried to hold revivals in the sprawling metropolis, but had come up short. The men reached out to Graham, they agreed on a plan, and preparations began. A huge tent was erected at the corner of Washington Boulevard and Hill Street some called “the Canvas Cathedral.”

“It was initially planned to be a three-week revival starting in late September and it was so successful it extended for a total period of eight weeks, all the way into November. He ended up preaching to 350,000 people in this large tent they had erected on a parking lot in downtown L.A.”

In some ways, Los Angeles became the perfect setting for Graham’s message. “Its image as the hedonistic playground of Hollywood’s elite offered an easy target for Graham’s moral warnings,” Young maintains.

“If Sodom and Gomorrah could not get away with sin,” Graham preached, “neither can Los Angeles!”

The large crowds were noticed and it became a big media story. “Many Hollywood celebrities and movie stars came to the revival and many of them got saved. That added to the spectacle of it all and the newsworthiness of it all,” Young notes. Among those saved were Roy and Dale Evans and Louis Zamperini.

Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst – not known to have any religious affinities or affiliations — heard about the Crusade and was intrigued by the fact that movie stars were being converted. He put out the word to all his newspaper editors in a famous telegram that instructed: “Puff Graham.”

“Graham was on the front page of newspapers across the country overnight,” Young recounts. “It made him famous and it made him almost a household name. It set him up really well for the revivals he was conducting afterward.

“L.A. was really the turning point in his life and Billy Graham saw it as the turning point in his career life. In his autobiography he called the chapter about L.A., ‘watershed.’”

As God used Pharaoh and King Cyrus for his purposes, so he used ‘Citizen Hearst.’

“Hearst made him famous, maybe a lot sooner than he would have been. Hearst was a huge figure in this story. Hearst was a great salesman and he knew a great story when he saw it. He saw a new star on the horizon.”

“As Graham preached his last sermon in Los Angeles that autumn, he seemed to sense how profoundly the city had transformed his ministry and altered his destiny,” Young notes.

Graham recognized it himself. “The revival that started here won’t end with the folding of this tent,” he said. “This is not it yet, but it will come.”

“He entered Los Angeles a virtual unknown, and he left it almost a household name. His team quickly dispatched the canvas tent for packed stadiums in major cities around the world.”

Billy Graham maintained a sterling reputation throughout his ministry life and became a friend to every president from Truman to Obama. “Graham never had a fall from grace that so many other public figures have had,” Young notes.

He did receive criticism, however, about his close friendship with President Nixon. “The most difficult moment was his relationship with Nixon and he felt very embarrassed about what came out in the Watergate tapes,” Young says.

“He learned how uncouth Nixon was. He was mortified by Nixon’s foul language.” Graham was also embarrassed by comments he himself made on the Watergate tapes that were perceived as anti-Semitic.

“He was mortified by that,” Young says, but Graham also learned from the experience.

“He didn’t seek to cover it up. He recognized he got too close to political power and made some compromises he wasn’t comfortable with having made. It changed how he operated in terms of politics and presidents going forward.”

After Nixon, Graham “just wanted to be a spiritual advisor and spiritual comfort to those presidents and to not seek political influence or power because the Nixon episode had shown him the real downside of that.”

Perhaps less well known is that Graham ministered to the Clintons during the Monica Lewinsky scandal. “That demonstrates he really saw his work, the impact, was more to meet their spiritual needs, to be a spiritual resource to them as opposed to any political influence.”

“I don’t think there will ever be another Billy Graham in the ways we’ve imagined his life and career and influence. He was America’s pastor. That meant he was the pastor that all Americans knew and all presidents knew to turn to.”

“For all his fame, Graham’s message remained the same: Individuals need to repent of their sins and accept God’s free gift of eternal life through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.”

Neil J. Young is author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.” He co-hosts the history podcast Past Present.