by Kim Farr, The Seed Company —

“What happened to you?” Berki Banko’s mother faced her exhausted, bloody son. He’d just found his way home after nearly dying in the Ethiopian wilderness.

To his mother, Berki was still lost. His choices had brought shame to their family and she was desperate.

“Berki, this breast nursed you when you were a child,” she said, clasping her left breast with a weathered hand. “My body and this breast gave you milk ─ gave you life. How can you turn your back on us now?”

At age 19, the time had come and gone for Berki’s rite of passage to manhood. Among the Hamer people of southwestern Ethiopia, that means bull jumping. The village gathers. The women, backs bare, chant and blow horns in hopes of provoking the boys to whip them with birch sticks. The permanent scars become a symbol of devotion — though some women have even died from the beatings, Berki says.

Next, each boy runs naked toward a line of bull cattle standing side by side. Vaulting himself, he runs across their backs. If he falls, he must endure public shame before trying again. If he makes it across all the bulls, he joins the fraternity of men who have accomplished the feat. He claims a bride (or several) and the right to father children and own cattle.

Having recently become a Christian, Berki recoiled at the thought of jumping. He remembered the sound of bells tied around the calves of dancing women. The days of feasting and drinking sorghum beer. The smell of dung rubbed across the bulls’ backs to make the jump more challenging. The goat sacrifices. Worst of all, he remembered the women’s bloodied backs as they sang: “I was beaten in a small way. Beat me more.”

The ceremony is full of things that don’t please the Lord, he thought.

He also knew what it would mean to say no. His mother couldn’t bear the humiliation.

“If you jump, you will be accepted,” she told him. “If you refuse, you are no longer part of us. Don’t bring shame on the family.”

“I can’t,” he answered. “You can kill me. I won’t jump.”

Tears stung Berki’s eyes as he walked away from his family, his village and his culture. He longed for them to find what he had found.

“If you don’t die,” his mother had told him, “I will die.”

CHANGE IN DIRECTION

Berki reminded himself that his spiritual family stretched beyond the borders of his village, Dembayte. He remembered the first time he’d seen a church. He’d walked 2.5 miles from Dembayte to sell milk in the nearby village of Turmi.

“What is this place?” he’d asked.

“This is God’s house and His children’s house,” one man said. When Berki returned home, he told his friends, “I saw God’s house. I didn’t see God but I saw His children.” From that day forward, Berki wanted to see God Himself.

Berki had been a slight child. His father said he was too weak to look after the cattle, so he sent Berki to Turmi when he was 16 to attend school instead. There, Berki met an Ethiopian evangelist named Segui, who told him about Jesus. Within a few weeks, he became a Christian.

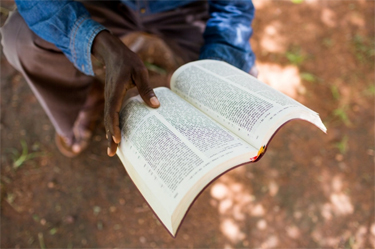

Later, when white-skinned missionaries came to Dembayte with Bibles in Amharic (Ethiopia’s official national language), Berki served as their translator since many of his people spoke only Hamer. But the missionaries saw few convert to Christianity. People from the nine tribes and languages of the South Omo Valley couldn’t understand why missionaries insisted they abandon their traditional culture and traditional clothing.

When Berki told his family about his new faith, his father dismissed the notion as part of his education … until Berki refused to eat the goats sacrificed in traditional religious ceremonies. Then his parents stopped supporting him financially. When the discouraged missionaries returned to Jinka — about a two-hour drive away — Berki went with them out of a desire to follow God and continue his education.

When Berki told his family about his new faith, his father dismissed the notion as part of his education … until Berki refused to eat the goats sacrificed in traditional religious ceremonies. Then his parents stopped supporting him financially. When the discouraged missionaries returned to Jinka — about a two-hour drive away — Berki went with them out of a desire to follow God and continue his education.

Low on money, Berki rented a room at a church compound. He often lacked enough to eat, eventually developing a stomach ulcer. For four months, Berki prayed for God’s healing.

Lying in bed one night, his stomach burned. Berki still isn’t sure whether what he saw next was a dream or a vision. He imagined a man coming into his room, aiming a large flashlight at his eyes. Berki begged the man to rid his body of pain. He imagined the man snapping on gloves, holding the flashlight steady and cutting into his torso. Berki envisioned his heart beating within his open chest. After the man pulled and tugged and washed the infected area, he closed the incision and Berki fell asleep.

The next morning, Berki’s pain was gone. He wept as he told his friends.

“God — or somebody — healed me! My body is totally normal and I don’t have any more pain.”

He remembers finding a piece of paper and writing: “My parents and my brothers could not help me, but what can I say? You, God, have helped me.”

It wouldn’t be the last time he’d thank God for sparing his life.

Wilderness

“Jump over the bulls. Marry somebody. Live with us.”

Berki had completed high school, left Jinka and returned to his home region to teach school. His family persisted. But he wouldn’t consider the thought.

After eight months of teaching and family tension, Berki sensed a strong prompting: Leave this job and go to Dimeka.

“Who are you?” he asked. “What do you want me to do?”

Believing the directive to be from God, Berki packed his things early the next morning and moved to Dimeka, a town 17 miles to the north.

As soon as he arrived, he went to a church and prayed, “God, what is Your will for me?”

Berki resolved to work full time in ministry. He didn’t know where that would be, but he knew he wanted to give  his life to God’s work. Soon, he would receive a letter from the Ethiopian Kale Heywot Church district office offering him a position in the town of Alduba. He accepted.

his life to God’s work. Soon, he would receive a letter from the Ethiopian Kale Heywot Church district office offering him a position in the town of Alduba. He accepted.

Berki served a year there before his family again pleaded with him to return to Dembayte and jump the bulls.

“You must choose one of the two,” they told him. “If you jump, you will be part of the family and live with us peacefully. If you refuse, you are no longer part of this family and we will kill you.”

“Don’t you know that I am an evangelist?” he replied. “I will never do this.”

Berki’s parents meant what they said. They consulted several witch doctors to plot how they could kill him. To their surprise, each told them not to touch Berki.

“Someone has given him the highest position,” one advised. “Don’t touch him. It’s as if he is the firstborn, though he is the third-born. Our powers cannot stand against him.”

A DANGEROUS EXPEDITION

Berki returned home to Dembayte for a visit. To his surprise, his family welcomed him warmly. He wondered if they had softened. Even Berki’s older brother, Gadi, seemed to set aside their differences.

“Brother, do you want to go with me to cut the honey?” he asked. Berki had always loved gathering and eating honey. Of course he would go.

The two set out before 6 a.m. the next morning, walking far from home into the heat of the day. Thirteen hours later, Berki’s legs ached. Dust covered his feet and his tongue clung to the roof of his mouth.

“When are we going to reach the place where we’ll cut the honey?” he asked. “It’s getting dark.”

“We are lost,” Gadi replied. “I don’t know the way.”

Berki longed to be home. With the orange sunset melting on the horizon, Gadi and Berki walked into a valley to find shelter in the shadows. Gadi told him to rest while he walked a little way to see where they were.

What Berki didn’t know was that his family had told his brother to kill him.

Now, as the AK-47 rifle slung over Gadi’s shoulder grew heavier with each step, he agonized. Should he just leave Berki alone and tell the family that the nearby lions and hyenas had gotten him? Or should he finish this now?

Darkness closed and Gadi made his decision. As heavy rain began to fall, Berki realized his brother had left him. He climbed out of the valley to see if he recognized any landmarks. Nothing. He called out in vain for his mother.

Thunder crashed around him. Terrified, he sat in the mud and began to cry. Then he raised his arms skyward. God, only You can help me. It’s late in the day and I am far from home. Lord, take me now. It is better for You to take my life than for me to be eaten by wild animals.

As Berki tried to stand again, he realized a river of sand and mud had swallowed his right leg like concrete. No matter how hard he tugged, he couldn’t move.

Delivered

Stuck in the mud and exhausted, Berki pleaded with God.

Lord, if You don’t take me, help me sleep. I don’t want to be awake if the wild animals attack me.

Soon, sleep overtook him. When he felt the sun’s warmth on his face, he opened his eyes to find he had slept the whole night.

Praise God! I’ve slept as if I were home in my own bed, he thought. No words can express my joy. My night has become day.

Still stuck, Berki tugged to free himself. A large rock sliced open his knee as he mustered strength to stand. As he bent to examine the wound, he looked at the mud surrounding him.

Hyena tracks. Everywhere. The deadly beasts had paced around his sleeping body all night but had not attacked.

Berki climbed to the top of a nearby mountain and breathed a grateful prayer.

You have saved me! From now on I will serve You above all above all else, he vowed. It is better to be at the main gate of your house than in the company of my own family. You, O God, are above all. You are more to me than my parents. More than my relatives. More than my brothers and sisters.

With renewed strength, Berki began the long walk home. To his mother’s dismay, he arrived home before his brother.

“What happened to you? What about your older brother?”

At her wits’ end, she swore her own death if Berki lived.

At her wits’ end, she swore her own death if Berki lived.

That was about a decade ago. Berki’s family refused to recognize him as a human being because he wouldn’t jump the bulls. He found a place to live in nearby Turmi, where he would marry and have a son.

“I know that God called me for His purposes,” he says. “He drew me out of my family and rescued me from all harm because of His great love.”

Berki’s parents both have died now — his mother recently, from cancer in her left breast.

IMPACTING HIS PEOPLE

Two years ago, a leader from the Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church’s Hamer district recruited Berki to attend an Oral Bible Storytelling workshop. There, he learned to tell accurate Bible stories.

Today, as a full-time evangelist, Berki dons traditional clothing and rides his bicycle to nearby villages to tell Bible stories. Typically that’s one-to-one, to keep cultural tensions down. But people welcome him. He’s one of them.

He’s even growing his beard for credibility, considering his small stature.

“To be clean-shaven in the Hamer culture means that you are a kid,” he says.

Berki still visits his family, bringing coffee and telling Bible stories. They listen, but they still reject his wife, Terefra, and their only son. “Until a man jumps, his marriage and children are illegitimate,” his brothers maintain.

He holds out hope, though, based on the changed lives he sees around him.

“I am a thin man but God is a big God. He is working through me. Before, many refused to listen to what the Bible says. Since people have seen God at work in my life and since they have heard Bible stories in their own Hamer language, they want to know more about Jesus.”

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

This story originally appeared in Seed Company’s Co:Mission periodical. Seed Company is a Wycliffe Bible Translators affiliate. Story and photos used by permission.