By Michael Ashcraft and Mark Ellis

With a monsoon ahead and the Japanese army in hot pursuit, Lt. General Joe Stilwell trekked 140 miles through steamy jungles and over 7,500-foot mountain ridges to escape from Burma during World War 2.

His party of 117 carried money and Tommy guns, but their secret weapon was the voices of 19 Gospel-singing Burmese nurses. Despite battling tuberculosis, Than Shwe, a devout Christian, led the hardy women in “Onward Christian Soldiers” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to boost morale in the flagging marchers.

“’Sing, girls, sing,’ Uncle Joe would say,” Shwe related to Stars and Stripes. And so they sang throughout their flight from the Japanese.

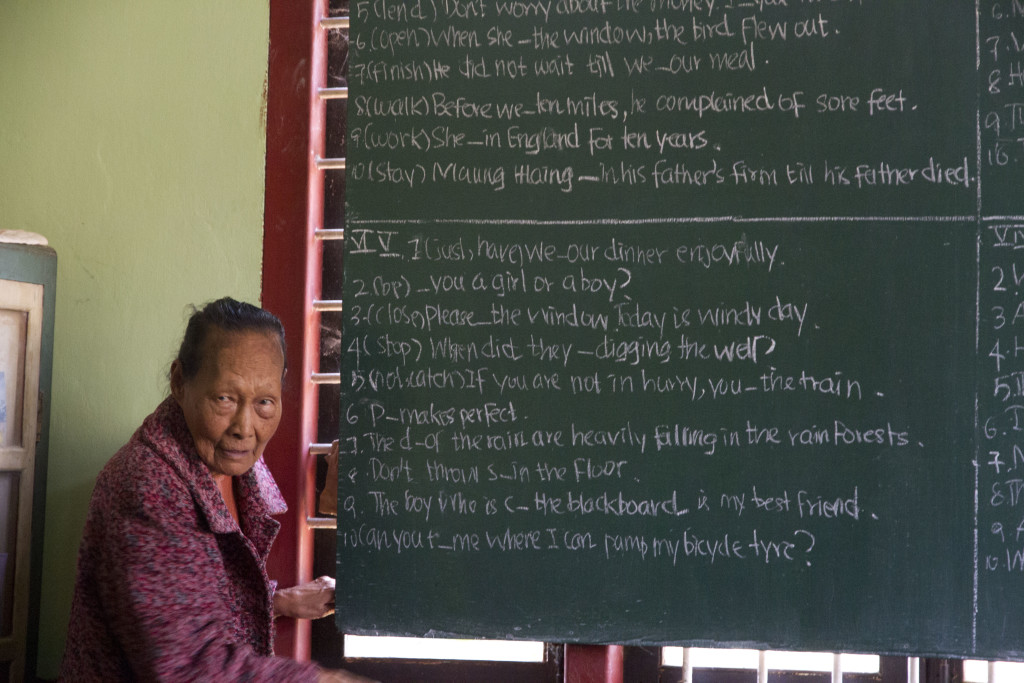

Shwe was still teaching English in Myanmar, at 89-years-old when she was interviewed two years ago. Although she shares the same name as the ex-dictator of Myanmar (Burma), Shwe has nothing else in common with the repressive military general who handed leadership over only recently.

She is remembered for being peppy and cracking jokes. Hardworking, she offered her services as a nurse during World War 2 despite fighting her own battles against TB.

Stilwell’s retreat on foot from Burma in May 1942 is the stuff of legends among history buffs. The no-nonsense general who wore no military insignia to show solidarity with his troops led the Allies in the China-Burma-India theater.

He sent much of his staff out of the country on planes but refused this easy path for himself. Instead, he led the foot-retreat personally. “I prefer to walk,” he said.

When Stilwell – known to his soldiers as “Vinegar Joe” for his acid personality – found his forces disintegrating, he was obliged to retreat. On May 6, leaving Indaw, the group headed west into the impenetrable jungle, tromping a minimum 14 miles a day through mud and zig-zagging up and down switchbacks to India.

“The jungle was everywhere,” wrote Donovan Webster in The Burma Road. “Its vines grabbed their ankles as they walked. Its steamy heat sapped their strength. And every time they reached the summit of yet another six-thousand-foot mountain, they could only stare across the quilted green rain forest below and let their gazes lift slowly toward the horizon. Ahead of them, looming in the distance, they could finally see the next hogback ridge between them and safety. They would, of course, have to climb over that one, too.”

Stilwell was committed to assuring that every member of his party – Americans, English, Indians, Chinese and Burmese – escaped alive. Japanese troops, trying to cut off Chiang Kai-Sheck’s supply line through Burma, were chasing him from the South, the East and the Northeast.

“By the time we get out of here, many of you will hate my guts,” Stilwell said. “But I’ll tell you one thing: You’ll get out.”

The nurses looked frail, hardly apt for such a rigorous journey, and Stilwell urged anyone incapable of completing such an arduous journey to stay behind and seek refuge in town. But instead of slowing up the group, the gospel-singing nurses turned out to be a godsend, constantly injecting enthusiasm with their lively songs.

Than Shwe, debilitated by the TB, had to be dragged down the river on an inflatable mattress for parts of the journey. But she proved herself stronger than many, despite being beset by disease.

The pursuing Japanese were only half the problem. The other was the oncoming monsoon season, which threatened to turn their road forward into a muddy quagmire and streams into impassable torrents.

A Chinese mule train was procured to help with carrying supplies and anyone who might get sick – malaria and dysentery would plague them all. The withering heat of the midday sun made even the American officers fall over face first – unconscious — into the vegetation. They survived on porridge, rice, corned beef and tea.

On May 8, Japanese bombers overhead sent everybody scurrying for cover. On May 9, the group reached Maingkaing on the Uyu River. Stilwell purchased rafts from the village chief, hoping they could simply float downriver to make the journey easier, but they needed to strenuously pole their crafts forward for significant portions of the route.

After two days of poling, Stilwell and the bulk of the party found their rafts falling apart and the monsoon rains starting to fall on them. Nevertheless, they reached Homalin on May 11. To continue westward into India, they had to ford the mighty Chindwin River.

Stilwell marched northward in search of a way to cross it. “Stilwell bit down on his cigarette holder and frowned, glaring at the river as if by sheer force of will he could compel some form of river craft to appear,” said Coronel Dorn, quoted on History Net. “Suddenly, five dugout canoes and a freight boat nosed around a bend half a mile up the angry surge of water.”

Hailing the vessels, they crossed and escaped the clutches of the Japanese, who arrived in Homalin only 36 hours later.

Stilwell led the group up the long climb to Kawlum, where finally they were met by an expedition of British soldiers bringing them fresh supplies, including a doctor and ponies for the sick to ride. The trail forward climbed to 7,500 feet.

On May 20, Stilwell reached Imphal in India. It had been bombed the day before by the Japanese. Stilwell had lost 25 pounds and was suffering from jaundice. He was losing his eyesight.

When he arrived in New Dehli on May 24, crowds of reporters met him to hear of his amazing escape. But Stilwell scowled. There should be no congratulations for a retreat, he figured.

“We got a hell of a beating,” he said. “We got run out of Burma, and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

Fifty years later, Than Shwe showed off a Bronze Star issued to her by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt for her bravery in joining the war effort and for aiding in the retreat. How did she survive the journey while suffering TB?

“My God is very powerful,” she said.

Note: Sources for this report include Wikipedia, History Net, Stars and Stripes and The Burma Road.