By Rosie Beal-Preston, Christian Medical Fellowship

Jesus of Nazareth taught: ‘Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.’ (Matthew 25:40)

Before Christianity emerged, there were several hospital-like centres in Buddhist regions. The ancient Greeks practised a very simple form of medicine and Greek temples included places where the sick could sleep and receive help. The Romans are believed to have established some military hospitals. However, it was the Christians of the Roman Empire who began to change society’s attitude to the sick, disabled and dying, by their radically different outlook.

The Graeco-Roman world in which Christianity appeared was often cruel and inhumane. The weak and the sick were despised. Abortion, infanticide and poisoning were widely practised. The doctor was often a sorcerer as well being a healer and the power to heal equally conferred the power to kill. Among the pagans of the classical world only the Hippocratic band of physicians had a different attitude to their fellow human beings. They swore oaths to heal and not to harm and to carry out their duty of care to the sick.

However, it wasn’t until Constantine granted the first Edict of Toleration in AD 311, that Christians were able to give public expression to their ethical convictions and undertake social reform. From the fourth-century to present times, Christians have been especially prominent in the planning, siting and building of hospitals, as well as fundraising for them. Cities with significant Christian populations had already begun to change prevailing attitudes, and were already beginning to build hospices (guest houses for the sick and chronically disabled).

Stories of Christian caring had enormous impact, even before Constantine’s decree of toleration. Clement, a Christian leader in Rome at the end of the first century of the Christian era, records how the Christian community was already doing much to relieve the plight of poor widows. In the second century when plague hit the City of Carthage, pagan households threw sufferers onto the streets. The entire Christian community, personally led by their bishop, responded. They were seen on the streets, offering comfort and taking them into their own homes to be cared for. A few decades after Constantine, Julian, who came to power in AD 355, was the last Roman Emperor to try to re-institute paganism. In his Apology, Julian said that if the old religion wanted to succeed, it would need to care for people even better than the way Christians cared.

As political freedom increased, so did Christian activity. The poor were fed and given free burial. Orphans and widows were protected and provided for. Elderly men and women, prisoners, sick slaves and other outcasts, especially the leprous, were cared for. These acts of generosity and compassion impressed many Roman writers and philosophers.

In AD 369, St Basil of Caesarea founded a 300 bed hospital. This was the first large-scale hospital for the seriously ill and disabled. It cared for victims of the plague. There were hospices for the poor and aged isolation units, wards for travellers who were sick and a leprosy house. It was the first of many built by the Christian Church.

In the so-called Dark Ages (476-1000) rulers influenced by Christian principles encouraged building of hospitals.

Charlemagne decreed that every cathedral should have a school, monastery and hospital attached. Members of the Benedictine Order dedicated themselves to the service of the seriously ill; to ‘help them as would Christ’. Monastic hospitals were founded on this principle.

In the later Middle Ages, in cities with large Christian populations, monks began to ‘profess’ medicine and care for the sick. Monastic infirmaries were expanded to accommodate more of the local population and even the surrounding areas. A Church ban on monks practising outside their monasteries gave the impetus to the training of lay physicians. It was contended that this interfered with the spiritual duties of monks. So gradually cathedral cities began to provide more large public hospitals with the support of the city fathers and this moved medical care more into the secular domain.

Nevertheless, expansion of health care by the secular authorities continued to be challenged and stimulated by the Church’s example. Eventually there were few major cities or towns were without a hospital. And there were particular diseases, such as leprosy, where the Church, inspired by the example of Jesus who made a point to touch and heal these outcasts from society, took a lead. The Church built countless leprosy isolation hospitals. Even though actual medical knowledge was meagre when compared to modern standards, the efforts of the Christian Church nevertheless brought relief and mitigation of suffering to thousands of sick people. And perhaps just as importantly, it heralded a new, more humane attitude to the sick and elderly.

In England suffering was caused when King Henry VIII suppressed the monasteries. The Reformation deprived many suffering and disabled people of their only means of support. Patients of hospitals like St Thomas’ and St Bartholomew’s, founded and run by monastic orders, were thrown onto the streets. The onus for health care was placed firmly on the City Fathers and municipalities were forced to pay more attention to the health problems of the community.

It was not until the eighteenth century that the Christian hospital movement re-emerged. The religious revival sparked in England by the preaching of John Wesley and George Whitefield was part of an enormous unleashing of Christian energy throughout ‘Enlightenment’ Western Europe. It reminded Christians to remember the poor and needy in their midst. They came to understand afresh that bodies needed tending as much as souls.

A new ‘Age of Hospitals’ began, with new institutions built by devout Christians for the ‘sick poor’, supported mainly by voluntary contributions. The influence of this new age was felt overseas as well as in England. Health care by Christians in continental Europe received a new impetus. The first hospitals in the New World were founded by Christian pioneers. Christians were at the forefront of the dispensary movement (the prototype of general practice), providing medical care for the urban poor in the congested areas of large cities.

The altruism of these initiatives was severely tested when cholera and fever epidemics appeared. Larger

hospitals often closed their doors for fear of infection. While wealthy physicians left the cities for their own safety, doctors and the staff of these small dispensaries, driven by Christian compassion, remained to care for the sick and dying. Christian philanthropists inspired setting up the London Fever Hospital to meet the desperate needs of those living without sanitation in overcrowded tenements. Christian inspiration continued to identify specific needs, leading to opening of specialist units: maternity and gynaecology hospitals, and institutions for sick and deserted children. When the National Health Service took over most voluntary hospitals, it became clear just how indebted the community was to these hospitals and the Christian zeal and money that supported them over centuries.

Advance of medical knowledge

As well as taking a leading role in caring for the sick, Christians also played very important part in the furtherment of medical knowledge. Together, Jews and Christians took the lead in collecting and copying manuscripts from all over Europe after the burning of the Great Library at Alexandria. This rescued much medical knowledge for the religiously tolerant Arabic Empire and for later generations.

During the Dark Ages, Arabic medicine advanced considerably due to their access to these documents. In Europe, however, progress was comparatively slow. It was Christian thought that led to the formation of the Western universities. Founding of medical faculties was often due to Christian initiative. So too were attempts to raise standards of research and care.

During this period, the field of surgery saw most progress. Christians were among those advocating the need for cleanliness and less use of the cautery in treating wounds. Chauliac, the author of Chirugia Magna (Textbook of Surgery) was a priest and surgeon, who made many advances in orthopaedics. He led by example, staying at his post to investigate the plague and treat its victims when many of his colleagues fled.

In the Middle Ages there emerged a clash between those who relied dogmatically on ideas and theories passed on from Classical sources, and the new attitudes to research fostered by the growing influence of what is now called modern science. Christians such as Grosseteste, Bacon and Boyle encouraged experiment instead of simply relying on old traditions. The Royal Society was founded to encourage research, and the majority of its early members were Puritan or Anglican in origin. The discovery of printing (the first printed book in Europe was a Bible) and the Reformation sparked by Martin Luther were major forces in promoting intellectual liberty, and by the sixteenth century medical progress was advancing rapidly.

Many very important discoveries in many medical fields were made by people who held a Christian commitment and there is not room to mention them all here: William Harvey (circulation), Jan Swammerdam (lymph vessels and red cells) and Niels Stensen (fibrils in muscle contraction) were all people of faith, while Albrecht von Haller, widely regarded as the founder of modern physiology and author of the first physiology textbook, was a devout believer; Abbe Spallanzani (digestion, reproductive physiology), Stephen Hales (haemostatics, urinary calculi and artificial ventilation), Marshall Hall (reflex nerve action) and Michael Foster (heart muscle contraction and founder of Journal of Physiology) were just some among many others.

The same can be said of the advance of surgical techniques and practice. Ambroise Pare abandoned the horrific use of the cautery to treat wounds and made many significant surgical discoveries and improvements. The Catholic Louis Pasteur’s discovery of germs was a turning point in the understanding of infection. Lister (a Quaker) was the first to apply his discoveries to surgery, changing surgical practice forever. Davy and Faraday, who discovered and pioneered the use of anaesthesia in surgery, were well known for their Christian faith, and the obstetrician James Simpson, a very humble believer, was the first to use ether and chloroform in midwifery. James Syme, an excellent pioneer Episcopalian surgeon, was among the first to use anaesthesia and aseptic techniques together. William Halsted of Johns Hopkins pioneered many new operations and introduced many more aseptic practices (eg rubber gloves), while William Keen, a Baptist, was the first to successfully operate on a brain tumour.

Clinical medicine and patient care

It is not surprising to find that, again, due to their commitment to love and serve those weaker than themselves as Christ did, people of faith were at the forefront of advancing standards of clinical medicine and patient care throughout the ages. Thomas Sydenham is sometimes hailed as the ‘English Hippocrates’. He stressed the

importance of personal, scientific observation and holistic care for patients, and he was one of the brave ‘plague doctors’ who did not desert the sick and dying during the Great Plague of London. Herman Boerhaave followed in Sydenham’s footsteps, and was very influential in pioneering modern clinical medicine, while William Osler taught all medical students to base their attitudes and care for their patients on the standards laid down in the Bible.

Medical ethics

The Hippocratic ideal was expanded by doctors such as Thomas Browne (seventeenth-century), a godly physician who was one of the first to write on medical ethics and whole-person care. Thomas Percival, a zealous social reformer as well as a physician of integrity, drew up the first professional code of ethics in the eighteenth-century. From that time Christian thought has shaped much of the modern profession’s ethical conduct, promoting personal integrity, truthfulness and honesty.

Many early GPs were religious men, and non-believers often unconsciously continued to follow the prevailing general principles of Christian ethics. Two devastating world wars, followed by increasing secularisation and humanistic thought, combined with rapidly advancing ability to perform new medical procedures, have brought about unprecedented ethically uncertain situations. Bioengineering, genetics and surgery urgently require new codes of ethics, and many of the current laws and suggestions by regulatory bodies have been influenced by the Christian attitude and outlook.

Specialities

The Christian contribution to the many specialist branches of medicine is huge. There is only room to mention a few, such as Laennec, a Catholic, who invented the stethoscope. The emerging practice of orthopaedics was much enhanced by the Lutheran Rosenstein’s textbook on the subject, while the devout Underwood’s Treatise on the Diseases of Children became a classic. Still’s disease was named after George Still of King’s College Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital, who was a Lutheran and a vigorous supporter of Barnardo’s homes. In the field of dermatology, Willan (who wrote a history of Christ) was the first to classify skin diseases, while many Christian clergymen-physicians such as Blackmore, Willis and Fox were pioneers in the of advance of psychiatry. In the USA Daniel Drake, an Episcopalian, was among the first to study geographical pathology, and WH Welch of the Johns Hopkins, was an outstanding Christian pathologist who discovered the bacillus of gas gangrene. JY Simpson, Howard Kelly and Ephraim McDowell, all devout believers, were towering figures in obstetrics and gynaecology. Whilst most medical advances and discoveries have taken place in hospitals, numerous general practitioners such as Sydenham, James Mackenzie and Clement Gunn worked tirelessly in day-to-day practice, striving to embody the ideals of Christianity in their ethics and care of their patients.

Public health, preventative medicine and epidemiology

Early on Christians realised the connection between health and hygiene. Girolamo Fracastoro, a very versatile student in the sixteenth-century, began to investigate the spread of contagious diseases. In the next century his work was continued by Thomas Sydenham. Ministers advocated personal hygiene. It was John Wesley who said ‘Cleanliness is, indeed, next to Godliness.’ The social activism of the Quakers is well-known, among them John Fothergill who campaigned to eliminate social wrongs on grounds that they undermined the health of the people. Another Quaker, John Howard, had a great concern for prisons, where overcrowding and typhus were rife, and successfully promoted two prison reform Acts of Parliament. Edward Jenner, a devout man, was responsible for the beginnings of immunology and in ridding the world of the scourge of smallpox.

Social need

In the nineteenth-century, the Industrial Revolution had led a drift to the inner cities and intense social needs among the poor. It was the Quakers, Evangelicals and Methodists who in particular applied themselves vigorously to meeting these needs. A nation wide movement of Christian missions to help the poor was founded. Huge sums of money was raised by voluntary subscriptions. And armies of volunteers went to slum areas to offer practical help. Attention was paid to the misfits of society, such as drunkards, criminals and prostitutes, as well as homeless teenagers.

The Salvation Army, founded in 1865 by William Booth, provided much-needed medical care in impoverished inner city areas and homes for women who had been induced into prostitution. Unmarried mothers were cared for, and these projects have spread all over the world. Great Ormond Street Hospital was founded by Charles West, a Baptist, to meet the needs of sick children who were inadequately cared for by ‘habitually drunk (nurses) with easy-going, selfish indifference to their patients, and no knowledge or skill of nursing.’

Dr Thomas Barnardo set up his children’s homes after seeing the terrible plight of thousands of hungry and homeless children in the East End. Inner city missions bringing a combination of medical care and the gospel were set up. Christians were at the forefront of temperance movements. Care for the blind and deaf were areas drawing direct inspiration from Jesus. Use of Braille worldwide and schools for the deaf were pioneered by evangelical Christians.

St Joseph’s Hospice in Hackney, founded by the Sisters of Charity in 1905, was the prototype of the modern hospice movement. Dame Cicely Saunders founded St Christopher’s Hospice in 1967, with the aim of providing as peaceful an atmosphere as possible for those in their terminal illness, while offering an environment of Christian love and support.

Developing world missions

Jesus commanded his followers to go and make disciples of all nations (Matthew 28:19), as well as exhorting

them to love their neighbours as themselves. There have been several waves of missionary work during two millennia, and in each case medical work has played a key part.

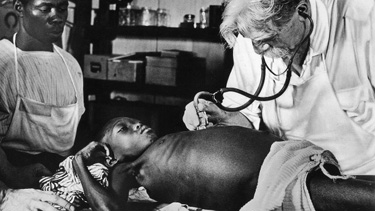

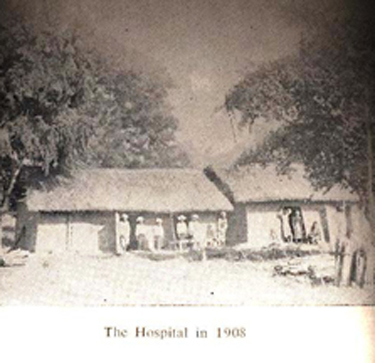

Dr John Scudder was among the first Western missionaries of the modern era and in 1819 went to Ceylon. Among the best-known pioneer medical missionaries were David Livingstone (Central Africa), Albert Schweitzer, a talented doctor, theologian and musician, who devoted his life to people living in the remote forests of Gabon, and Albert Cook, who founded Mengo Hospital in Uganda. William Wanless founded the Christian Miraj Hospital in India, and Ida Scudder founded the world-famous Vellore Medical College in the

same country. Hudson Taylor spread the gospel and western medicine to China and founded the China Inland Mission. Paul Brand pioneered missions to lepers. Henry Holland and his team, working in the north-west frontier of the Indian sub-continent, operated on hundreds of cataracts every day. Others have been influential in the prevention of such diseases as malaria and tuberculosis.

Women doctors

There was a strong Christian element in the motivation of the pioneers of medical education for women. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman doctor, was a Quaker, while Elizabeth Garrett came from a very devout family. Ann Clark, another Quaker, was the first woman surgeon and worked at the Women’s Hospital and the Children’s Hospital in Birmingham. Sophia Jex-Blake, another devout Christian, founded the London School of Medicine for Women, while Clara Swain was the first woman doctor to go overseas (to Asia) as a medical missionary.

Nursing

Modern nursing owes much to Christian influences. Most nursing, like most medicine, was carried out by monastic orders within their own hospitals for centuries. In AD 650, a group of devout nuns volunteered to take care of the sick at the Hotel Dieu in Paris, and most other nursing followed this pattern. In the seventeenth-century, a parish priest shocked by the conditions in the poor quarters of Paris, set up a nursing order under the name of Dames de Charite. Civic and secular authorities were somewhat slow to recognise the need for paid, rather than voluntary nurses. In the nineteenth-century, ‘modern nursing’ was born, in no small measure due to the work of Elizabeth Fry and Florence Nightingale. Their revolution in the practice of nursing included making it a more socially acceptable pursuit for women. Florence Nightingale was deeply influenced by a small Christian hospital at Kaiserswerth in Germany, run by ‘deaconesses’, a group of Protestant women. Their response to

biblical commands to care for the sick and educate neglected children, provided the templates for modern daily hospital nursing. Florence Nightingale encouraged better hygiene, improved standards and night-nursing, as well as founding the first nursing school. Nurses gained professional status at the end of the century, largely thanks to the work of Ethel Bedford Fenwick, with the majority of nurses being inspired to serve by Christian ethics. Many missionary nurses such as Mother Teresa and Emma Cushman have worked tirelessly, bringing hygiene and Western medicine to the four corners of the globe.

A new allegiance

This article has aimed to present some of the enormous contribution the followers of Christ have made to the science and practice of medicine. Christians have consistently raised the social status of the weak, sick and handicapped and sought to love and care for them to the utmost of their abilities. Christians have been pioneers among hospital building and staffing, in research and ethics, in promoting increased standards of care, and in immunology, public health and preventative medicine. They have carried Western Medicine across the globe and improved the quality of life for countless millions of people.

Christianity gives men and women a new perspective and allegiance; their lives are spent in joyful grateful service of the God who has redeemed them and given them new life. In many ways, Christianity and medicine are natural allies; medicine gives men and women unique opportunities to express their faith in daily practical caring for others, embodying the commands of Christ; ‘whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers of mine, you did for me.’ (Matthew 25:40)

References

- Aitken JT, Fuller HWC & Johnson D The Influence of Christians in Medicine London: CMF, 1984

- Hanks G, 70 Great Christians, Th199tory of the Christian Church; Christian Focus Publications 1988

- Wyatt J, Matters of Life and Death; London & Leicester IVP/CMF, 1998

Used by permission of the Christian Medical Fellowship