By Michael Ashcraft —

After he went blind, Ted Hinson got a job in natural gas exploration, played golf, ran marathons, went skiing and hunted deer.

After he went blind?

“Ted, I am your father, you are my son,” God told him after Ted went blind. “I always want the best for you.”

Ted Hinson, a Tulsa man, lost his sight unexpectedly in 1986 while he was married with one child and a petroleum landman, as narrated in his memoir Beyond the Blindness: My Story of Losing Sight and Living Life.

“Permanent?” Ted asked his neuro-ophthalmologist, who in July 1986 had just broken bad news about optic nerve damage from a rare virus.

“Permanent?” Ted asked his neuro-ophthalmologist, who in July 1986 had just broken bad news about optic nerve damage from a rare virus.

Consultations with a Baltimore specialist a month later confirmed the diagnosis.

“A rare, rare case,” the expert from John Hopkins University muttered.

“Not quite rare enough,” Ted thought to himself.

“Slowly it was sinking in that I was facing a future completely unimaginable just a few months earlier,” Ted recalls.

Almost naturally, he strengthened his relationship with God, deepening his commitment to God. He asked God, “Hey, God, remember me?” The Father responded with affirmation and with challenge for Ted to continue in faith.

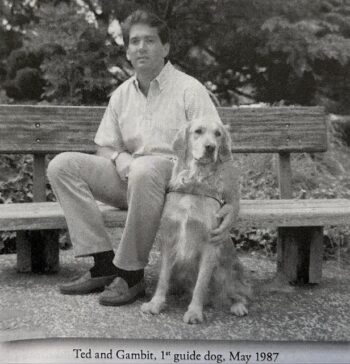

Getting the coaxing and encouragement from God, Ted got about living life. He went to school to learn braille, how to get around with a cane and ultimately how to get around with a guide dog. His first, Gambit, was “more than man’s best friend.”

Getting the coaxing and encouragement from God, Ted got about living life. He went to school to learn braille, how to get around with a cane and ultimately how to get around with a guide dog. His first, Gambit, was “more than man’s best friend.”

“I tried to look at the positive side of everything,” he says. “The only way to enjoy the parts of this different life was to move forward with what I had and not feel defeated by what I had lost.

“I don’t want to minimize the frustration and limits we as blind go through,” he adds. “It takes constant effort and some good, helpful people along the way.”

Ted didn’t mope. He got a braille watch, went drinking with his buddies and dancing with his wife. At dinner with friends one night, he meant to scratch his wife’s hiney but because he was blind misaimed.

Ted didn’t mope. He got a braille watch, went drinking with his buddies and dancing with his wife. At dinner with friends one night, he meant to scratch his wife’s hiney but because he was blind misaimed.

“Wrong rump!” he exclaimed. “After the initial embarrassment, we all enjoyed a good laugh.”

“I’d like to offer you a job,” Robert told him one day. “I like your background as a landman and I like your attitude.”

Ted couldn’t find words. The unemployment rate for the sightless hovered around 70%. How could he do it?

Robert informed him that there was new computer software that could read out loud emails and reports. This was way back in the beginnings of the technological innovations. Compared to Siri nowadays, the advances of that time seem primitive. But Ted was hired by Hutton Gas!

“It was unbelievable, a true miracle for us,” he remarks.

“It was unbelievable, a true miracle for us,” he remarks.

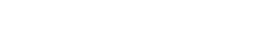

When he first became blind, Ted told his wife he didn’t want any more kids than his first, Matthew, because he wouldn’t be able to see them.

Apparently, God — and his wife — had other plans. Ultimately, Ted and Pat had five.

His buddy invited him to hit some golf balls at the range — and Ted discovered he was pretty much as good as always! (Which means, he was just as bad as he was before losing his sight.)

When he prospected clients on the phone, the issue of his blindness never came up. When he had to the meet them in person, Gambit was a great ice-breaker.

Ted was pretty much up for any adventure. So when a buddy invited him waterskiing, he replied, “Great, can’t wait!” They devised a system of using a whistle to warn of hazard, which would warn Ted to not make a sharp or wide cut.

Then his boss, Robert Hutton invited him to go running together.

“As we slowly jogged, I notice i had to be very conscientious about keeping my feet up, not getting lazy or tired and shuffling or dragging them,” he observes. “It wouldn’t take much to trip over a small lip in the path.”

Friends kept piling on the challenges: the Tulsa Run, the Tulsa Triathalon, the Houston Marathon. “Somehow I survived,” he says.

Snow-skiing was next, followed by deer-hunting.

For some reason, his buddies didn’t let him carry the gun around. But when it came time to shoot, the helped him aim and told him when to pull the trigger.

“BANG!” he recalls. “The next thing I hear was the gobble of an innocent, dying turkey.

“Jeez, who’s that? I’m sorry,” Ted said confused because he though it was deer. “What happened?”

“Sorry, Ted,” he partner responded, laughing. “We’re also hunting for turkeys. I got a little excited in the moment and just didn’t think to tell you.”

Later he got a deer too.

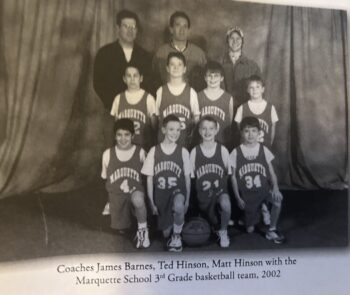

Nothing seemed impossible, so when his son, Luke, was in third grade, he volunteered to coach basketball. Why not? He’d been able to succeed in so many areas believed to beyond the reach of blind people.

“I couldn’t see to correct sloppy mistakes or bad shooting form,” he admits. “I just taught them the fundamentals. During game, I would shout, ‘Hands up on defense. Move your feet. Block out. Strong passes. Make yourself big.'”

Ted never told the other coaches or even the referees that he was blind — and they may not have realized it.

“Good talent makes any coach look pretty good,” he says. “Both teams did well all three years I coached.”

Going blind wasn’t the worst tragedy of his life. Losing his son, Matt, then 22, in a boating accident was. “No parent should ever have to attend their child’s funeral,” he says.

He missed Matt more than his sight.

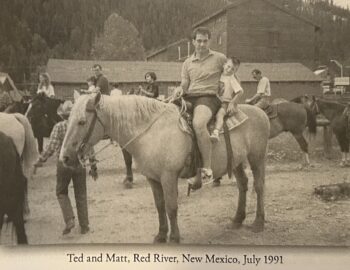

Life with Pat, a special ed teacher, and their kids has worked by team.

“Being bling is a real pain in the you-know-what for me and my family,” he says. “This is life…. Having these limits caused me to look deeper for other ways to live my life or creat methods in order to achieve things.”

Ted credits his wife, his friends and God with helping him through.

“In all honesty, I consider myself lucky,” he says. “I thank God everyday.”

To learn more about a personal relationship with Jesus, click here.

Related articles:

- Deaf missionary couple in Africa.

- Blind evangelist.

- Blind surfer.

- Colorblind artist.

- One-armed basketball player.

- A church for people with disabilities.

About this writer: Michael Ashcraft pastors a church in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles.