By Brian Nixon —

When my distant relative, Thomas Janney (1633-1697), arrived in the United States from England, he brought with him his budding faith—Quakerism, established by George Fox (1624-1694). After settling in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Janney preached the gospel of Christ, helping establish churches throughout the region.

Janney was invited to the United States by William Penn, the European (non-native) founder of Pennsylvania. Penn wrote Janney a letter, asking Janney’s family to immigrate to the New World. Though Janney died on a trip back in England, the denomination he was passionate about (formally, the Religious Society of Friends), went on to make a huge impact upon the infant United States, helping shape the outlook of the new country religiously, politically, and socially.

But one area of life that is not often associated with Quakerism is art, largely due to Quakerism’s stress on the unadorned simple life. But if one was to look closely enough—particularly in galleries across the United States in cities such as Brooklyn, Kansas City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Worchester, New York, and Newark—one would find the Quaker influence on art though the man Edward Hicks.

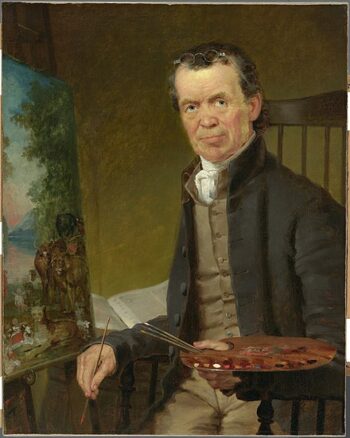

Born in 1780 in Bucks County, Hicks was raised by Elizabeth and David Twining, family friends, that nurtured Hicks in the Quaker faith (Hicks mother died when he was young, his father unable to care for his upbringing). Though wayward—as many teenagers are (“vain amusements” he called them)—Hicks committed his life to Christ in 1801 and was formally received into the Quaker family. By 1812, Hicks was a minister.

To help pay the rent and support his life as a minister, Hicks began to paint—signs and coaches. His life as a decorative painter led to his work as America’s preeminent folk artist. Of the hundreds of paintings he completed, sixty-two of them depict a scene from Isaiah 11:6-8. In the text, as in the paintings, a child is leading the animal kingdom.

Entitled The Peaceable Kingdom, the paintings define Hicks as an artist and theopoet, one who represents his theological beliefs via artistic means. The main difference between the Biblical text and Hicks’ painting is that Hicks often places Quakers and Native Americans (a peace treaty) within each work, a gesture, that in itself, has deeper theological meaning as we’ll see below.

The result is that Hicks created fascinating paintings, masterworks of early American art. As curator Sanford Schwartz writes, “Edward Hicks was the creator of one of the most familiar scenes in American art…”

By 1860, Hicks began to exhibit his work.

In addition to his Peaceable Kingdom series, Hicks painted other Biblical scenes, landscapes, historical works, and farm life. One characteristic common to all of Hicks’ paintings is the depiction of the outdoors. Many conjecture this was for metaphorical reasons (Quakers place a premium on light, and the light source is the sun or sky in his works). Furthermore, the color used in his works are simple, earth-like tones. Like with the use of light, color is a way that Hicks’ may have tried to insert his theological beliefs of peace, tranquility, and human—divine qualities, heaven and earth meeting with the coming of Jesus Christ.

At a recent exhibit at the Albuquerque Museum, I was able to see one of Hicks’ Peaceable Kingdom paintings (in all, I’ve viewed roughly six in person), part of the traveling exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

As one walks into the exhibit space, they are immediately confronted by two paintings—Hicks’ Peaceable Kingdom and Benjamin West’s (another artist loosely influenced by Quakerism, his parent were Quaker) entitled Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. As impressive and huge as West’s painting is (75 1/2 x 107 3/4 in.), my eyes kept coming back to Hicks. Maybe because the Peaceable Kingdom works have been a lifelong interest of mine, but more likely because of the theological implications inherent in his work. Hicks was a man who believed what he was painting. With Hicks, there are profound theological implications to his work: that Christ will return, bringing peace, ultimate reconciliation, including peace with the natural world. And though West’s painting is clearly more technically advanced, Hicks’ matches his head and hands to his heart, his beliefs manifest in his art.

My relative Thomas Janney preached with words; Hicks preached with words and art. Humanity is the better because of the message they proclaimed: that God has spoken through the incarnation, a message of reconciliation and peace.

As Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart reminds us, “The earliest confession of Christian faith…meant nothing less radical than that Christ’s peace, having suffered upon the cross…had been raised up by God as the true form of human existence…” And the result of Christ’s work in the world, a peace accord was established, reminding us that God’s truth, beauty, and goodness–“the true form of human existence”– is available to all who believe, and will one day be consummated in a Peaceable Kingdom.