By Brian Nixon —

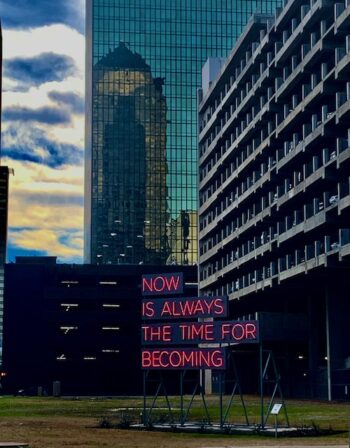

Down the street from the Dallas Museum of Art is a sign surrounded by skyscrapers.

On one side of the sign it reads, “Now is Always The Time for Becoming;” on the other side, “Now is Only for the Time Being.”

The sign is a work of art.

According to the Nasher Public arts initiative website, the artist Alicia Eggert uses material of commercial signage to explore “language and time.” Furthermore, Eggert takes “inspiration from astrophysics, existential philosophy, and semiotics,” to “question one’s experience of reality from a cosmic perspective.”

As I strolled down the street, the sign was a welcome interruption, causing me to ponder its meaning. Two words stood out: being and becoming.

According to Thomas Aquinas, being has various nuances or modes. One, being “subsists in itself.” It exists. Two, “subsisting being, as in the case of form.” Something exists according to a specific form. Three, a “disposition of a subsisting being…a quality.” Being has certain characteristics or qualities. And four, “a privation of a disposition.” These characteristics may have other conditions. Aquinas uses blindness of a human as an example.

Concerning being and becoming, Aquinas connects it to essence and existence. For Aquinas, essence and existence are distinct. Essence possesses existence but is not identical to existence. Dr. Richard Howe puts it this way: “A things essence is what it is. Its existence is that it is… Your essence is what makes you a human. Your existence is what makes you a being.”

I know—head scratching.

Here’s the thing to remember, there is a difference between being and becoming. One is connected to our existence (that we are), the other to the nature of being (what we are, our qualities and characteristics).

The study of being is called ontology. The Greek preface ōn means being, and logy means the study of. Ontology is a division of philosophy (metaphysics, to be precise) that deals with the nature of being, our existence.

Why bring this up? First, this is where my brain went when I read Egger’s sign-art. Second, because ontology is one of the important classical arguments for God’s existence. Though birthed in Greek philosophy, it was Anselm of Canterbury (d. 1109) that gave it its first full treatment, followed by Rene Descartes (c. 1596-1650), Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716), and others.

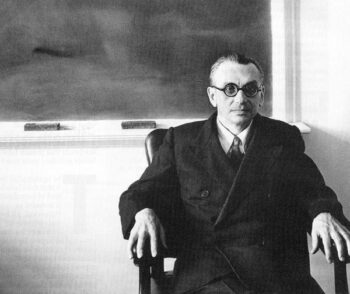

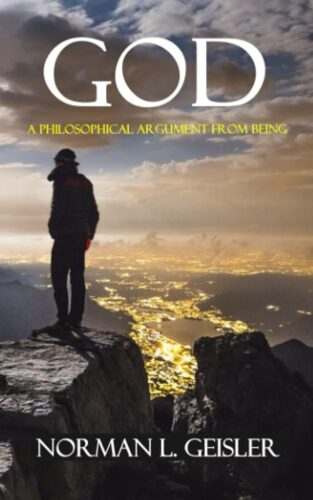

In our contemporary world, individuals such as Alvin Plantiga (b. 1932), Norman Geisler (1932-2019), and William Lane Craig (b. 1949) have presented version of the ontological argument. But it was the logician and mathematician, Kurt Gödel (1906-1978), that presented his version of the argument—using modal logic—that caught the attention of many within the scientific community. His work was demonstrated to be one-hundred percent accurate by German scientists.

So, what is the ontological argument? As noted, there are several versions. For the sake of simplicity, here’s Norman Geisler’s version taken from his book God: A Philosophical Argument from Being:

1) Being is. That is, something exists.

2) Being is being. A thing is identical to itself.

3) Being is not non-being.

4) Either being or non-being. Something cannot both exist and not exist at the same time.

5) Non-being cannot cause being. Nothing cannot cause something.

6) A caused being is similar to its Cause.

7) A being is either necessary or contingent but not both.

8) A necessary being cannot cause another necessary being to come to be.

9) A contingent being cannot be the efficient cause of another contingent being.

10) A necessary being is a being of Pure Actuality with no potentiality.

11) A Being of Pure Actuality cannot cause another being with Pure Actuality to exist.

12) A being that is caused by a Being of Pure Actuality must have both actuality and potentiality.

13) Every being that is caused by a being of Pure Actuality must be both like and dislike its Cause.

14) I am a contingent being.

15) But only a necessary being can cause a contingent being to exist.

16) Therefore, a Necessary Being (of Pure Actuality) exists who caused me (and every other contingent being there may be) to exist.

17) This Necessary Being of Pure Actuality (with no potentiality) has certain necessary attributes:

A) It cannot change (= is immutable)

B) It cannot be temporal (= is eternal)

C) It cannot be material (= immaterial)

D) It cannot be finite (= infinite)

E) It cannot be divided or divisible (= simple)

F) It must be an uncaused being since it is a necessary being

G) It must be only One being

H) It must be infinitely knowing (= omniscient) Being

I) It must be all-powerful (omnipotent) Being

J) It must be an absolutely morally perfect Being

K) It must be a personal Being

18) Therefore, one infinite, uncaused, personal, morally perfect, all-knowing, all-powerful Being who caused all finite being(s) to exist is what is meant by a theistic God. Hence, a theistic God exists.

In the end, the ontological argument poses that because there is being (existence) there must be a Greater Being, namely God. Being begets being.

Whether Alicia Eggert wanted to inspire an internal conversation about being and becoming (how her intentions were expressed on the website, she does), that’s one of the many role’s art plays in our world: it moves us, yes; but it causes us to think, contemplating our place in a world of existence and essence, of act and potency, of presence and personhood. The artist may not provide the details, but they sure present us with points to ponder.