By Brian Nixon —

According to longtime friend and literary collaborator, Diane Ossana, Pulitzer-winning novelist, Larry McMurtry, was an atheist. This would explain why—after his death in 2021—he didn’t have a funeral. Commenting in a Texas Monthly interview, Ossana states, Larry “felt that life should be lived as it occurred, rather than celebrated after death.”

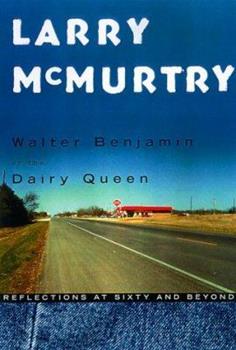

His belief clarifies why little attention was given to religious themes in his many novels. Even in his non-fiction works (my favorite), religious figures usually play minor roles. In his book of admiration for his hometown, Archer City (Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen), the clergy usually showed up only for dinner.

Concerning the lack of religious themes in McMurtry’s works, one commentator wrote regarding the Pulitzer-winning novel, Lonesome Dove, “Perhaps my only real criticism of the book is the almost complete absence of religious matters…”

In an interview with Benito Vila, McMurtry states, “I am in no way a spiritual person. I wrote a letter to the pastor of my Methodist church when I was in the fourth grade, explaining to the pastor I was quitting the church. I am a realist, an atheist, and I have no thoughts or opinions about spirituality or the afterlife, or what inspiration the stars may hold.”

McMurtry was a convinced kid. And though I could state various arguments for God’s existence, citing logicians, mathematicians, scientists, and philosophers, it’d be of little use—for a fourth grader or a man who passed away on March 25th, 2021. In other words, Gödel’s ontological argument won’t do much good here.

Theistic views aside, McMurtry was a legend in the Southwest—and beyond. It’s one of the reasons I drove to Archer City, Texas, staying at the fabled Spur Hotel (the owners were marvelous), seeing the famous Dairy Queen, and take in the Royal Theater (a place that found its way into the movie the Last Picture Show). But I drove to Archer City mostly to mourn the closing of his bookstore, Booked Up, which Chip Gaines purchased after McMurtry’s death, but has not re-opened.

I can’t claim to have read many McMurtry novels, but I have read numerous of his non-fiction works. Maybe when it comes to his novels, I’m like a writer I heard at a Western author’s event in New Mexico who commented—on a panel—that he can’t make it through many of McMurtry’s novels; they’re “unconvincing, historically speaking.” Not sure if that’s the case (again, I haven’t read many), but I do favor his nonfiction volumes.

As it happens, there’s many notable qualities I’ve gleaned from McMurtry. Here’s a few to comment on.

Fascination with Folks. Even if he didn’t believe in God, McMurtry was like God in that he created colorful characters; God does so physically, McMurtry on the page. People play an important role in McMurtry’s life—friends, family, and the occasional foe. Concerning friends, writing in Pastures of the Empty Page—a collection of essay’s honoring McMurtry—friend, Mike Evans, states, “The key to Larry’s range of friendships was that he liked to be entertained and he was nonjudgmental,” and that he was “breathtakingly generous” with people. Concerning foes, in the same book other contributors mention that McMurtry would get annoyed by people requesting autographs—especially when he was stacking books—or journalists that asked poor questions. Concerning family, he was loyal, unwavering. But with all people he had an open mind, conversational wit, and a general interest in the human condition, affording him a lifelong fascination with humanity. Because of this, people flourish in McMurtry’s books, the good, bad, in-between. Who could forget Call and Gus in Lonesome Dove; Sonny Crawford and Duane Jackson in the Last Picture Show; or Aurora and Anna Greenway in Terms of Endearment? People are the backbone of McMurtry’s works, as people are the image-bearers of God’s earthly creation. People matter—to both God and McMurtry.

Purveyor of Place. As mentioned above, McMurtry’s Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen is a love letter to Archer City, Texas (as well as to reading and books). His fist section of the book is entitled “Place—And the Memories of Place.” Place plays an important role in many of his works. McMurtry was proud of the place he came from—small, Northwest Texas cattle country. He bends over backwards in many of his nonfiction works to state that the place he was raised is the place that is most prominent in his mind—the landscape, the ranch, the sky, and Idiot Ridge (the small knoll by his childhood home). Paulette Jiles writes, “[McMurtry] was deeply rooted in North Texas, and his best work was drawn from the people and the landscape of that country.” Similarly, I think God is a lover of place. Not only did God create all places but meets people in particular places. Think of Moses on Mt. Sinai, or Paul on the Damascus Road. Places are important. As I quote theologian John Inge in my book Tilt: Finding Christ in Culture, “The incarnation affirms the importance of the particular, and therefore of place, in God’s dealing with humanity. Seen in an incarnational perspective, places are the seat of relations or the place of meeting between God and the world.” In other words, place matters.

Big on Books. I know Solomon reminds us that “of the making of books there is no end” (Ecclesiastes 12:12), but I’m still a fan of books. I read, collect, publish, and talk a lot about them. So did McMurtry. He was a book scout, a bookstore owner, and a bibliophile, having 450,000 thousand books housed in Booked Up in Archer City (most sold off after his death). As Bill Marvel writes in Pastures of the Empty Page, “Before He was anything else—cowboy, author, celebrity—Larry McMurtry was a man of books, a reader.” I happened to meet a contributor to Pastures of the Empty Page at the Spur Hotel, Kathy Floyd. Because of McMurtry’s love of books, a writer’s workshop arose–led by Floyd and George Getschow–in this small town of 1,600 people. They call the workshop “a living legacy to Larry McMurtry.” When it comes books, I’m a kindred spirit, relating to what author and Biblical scholar Desiderius Erasmus wrote, “When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes.” For a Christian—or any other person of faith—to be against books is self-contradictory, since most of the information we get from religious faith is found—or outlined—in books (in some cases, oral tradition). Without the Bible (a book), we’d have scant history of Abraham, Moses, Jesus, John, Paul—and a host of other Biblical figures. We may disagree with the content of some books but should never contest the character of books. Books matter, both to God and McMurtry.

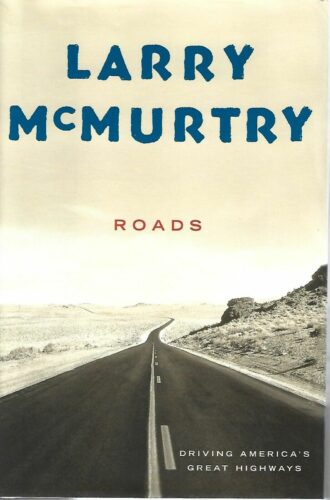

Riding the Road. Travel is every-present in the Bible. Abraham travelled; Moses travelled; Jesus travelled; Paul travelled. And, yes, Larry McMurtry travelled. Just read his book Roads. In the work, he travels various highways in the US—book scouting and just for the sheer pleasure of the open road. One of the oldest devices found in literature is the travel narrative, the hero’s quest, the journey of self-discovery. McMurtry was no stranger to the device. Travel is at the heart of Lonesome Dove (a cattle drive); travel is an important part of Cadillac Jack (an antiques scout); and travel plays an important part in McMurtry’s personal life. He traveled—a lot. By car. By plane. By train. Even after his bypass surgery (which left him in a deep depression, unwilling to read), he tried to get back to his “normal life,” which included “running bookshops, traveling, lecturing, writing fiction, writing movie scripts, and so forth.” Later in life, leaving collecting novels as his main pursuit, McMurtry turned his attention, to, among other topics, travel literature. Travel was important to McMurtry. To travel (to move) is part of what it means to be alive, to have being. I read in a Scottish history book that many lowland Scots (Scots Irish), were people prone to move and travel. Many eventually made it to America, continuing to travel across the United States. McMurtry mentions his families’ quest—from East to West—in several of his books. I know the Nixon’s (borderland Scots) did the same, making their way to Texas and California. To travel—and to talk about it—is to be human.

Riding the Road. Travel is every-present in the Bible. Abraham travelled; Moses travelled; Jesus travelled; Paul travelled. And, yes, Larry McMurtry travelled. Just read his book Roads. In the work, he travels various highways in the US—book scouting and just for the sheer pleasure of the open road. One of the oldest devices found in literature is the travel narrative, the hero’s quest, the journey of self-discovery. McMurtry was no stranger to the device. Travel is at the heart of Lonesome Dove (a cattle drive); travel is an important part of Cadillac Jack (an antiques scout); and travel plays an important part in McMurtry’s personal life. He traveled—a lot. By car. By plane. By train. Even after his bypass surgery (which left him in a deep depression, unwilling to read), he tried to get back to his “normal life,” which included “running bookshops, traveling, lecturing, writing fiction, writing movie scripts, and so forth.” Later in life, leaving collecting novels as his main pursuit, McMurtry turned his attention, to, among other topics, travel literature. Travel was important to McMurtry. To travel (to move) is part of what it means to be alive, to have being. I read in a Scottish history book that many lowland Scots (Scots Irish), were people prone to move and travel. Many eventually made it to America, continuing to travel across the United States. McMurtry mentions his families’ quest—from East to West—in several of his books. I know the Nixon’s (borderland Scots) did the same, making their way to Texas and California. To travel—and to talk about it—is to be human.

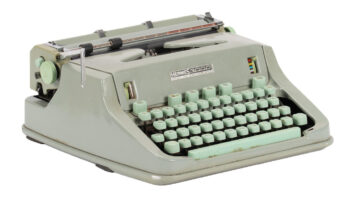

Toting Typewriters. As I write this (yes, on a computer), I have a shirt on that reads “Viva La Tecnologiá Muerta,” which translates as “Long Live Dead Technology.” I bought the shirt from Basement Films, an Albuquerque-based organization that specializes in reel-to-reel film and technology, hosting a yearly experimental film festival, Experiments in Cinema. Besides, my son, Isaiah, runs a club at a local high school called the Analog Club. Got to support the cause! This said, I enjoy old technology, the look, the engineering, and the history of it. Be it reel-to-reel, LP’s, VHS’s, trains, bicycles, watches, clocks, film cameras, or typewriters—there’s something nostalgic and beautiful about machinery of the past. Hence, my respect for McMurtry’s love of typewriters. His Hermes 300 even made it—in reference—to the Oscars. In his acceptance speech for Brokeback Mountain (best adapted screenplay), he thanked his typewriter, promising to give it “a big, wet kiss.” McMurtry carried his typewriter with him when traveling, writing five pages a day, seven-days a week. Old technology isn’t better than new technology, but old technology gives insight into human ingenuity, historical markers in our quest to know and understand, and dare I say, to mimic the mechanisms of God. To find the fingerprints of the inventors and the way in which he or she engineered the technology, the creator connected to its creation, technology allows us to—as the etymology of the word suggests—apply the systematic treatment of art and craft to life, studying its form and function, getting a glimpse of the mind behind the instrument, what, in theology, we call teleology.

Much more can be said about what I admire in McMurtry, but I’ll stop. I know some pundits may note he wrote explicit passages, sensually speaking. My answer: so did Solomon. Here’s the thing: As an atheist, McMurtry would disagree with some of what I pose above, particularly as it relates to God, and he surely wouldn’t—or didn’t want to— act like a Christian; he wasn’t one. So, to expect wholesome, devotional literature from a non-Christian is like asking a devout Muslim to wax eloquent on the Trinity. It rarely happens. McMurtry gave the world what his worldview required, a realist portrait of life with added eloquence and imagination (which, by the way, in conjunction with consciousness, qualities atheist have a difficult time explaining).

But as a Christian, I thank God for McMurtry. Though I disagree with his worldview, my worldview calls me to love all, even enemies. And though McMurtry was not a personal enemy, his worldview was in opposition to theism. Even here, I’ll let love lead. It’s also true that I gleaned most of these qualities mentioned above from other people first—and not McMurtry—but the fact that atheist Larry McMurtry valued them as well, brings joy to my heart. We may disagree on an essential understanding of life, but with common grace in view (grace given to all), God’s gifts apply to theist and atheists alike. Ultimately, I’m glad McMurtry believed in something. For in the end, nothing can’t create something, but something—or, better yet, Someone, can, and I’m glad that Someone created Larry McMurtry.

Postscript: I drove to Addison, Texas to InkQ Rare Books, LLC. InkQ purchased McMurtry’s personal collection of books, all having his family spur bookplate inside. After hearing marvelous stories from the clerk (Blake), I decided to purchase one of Christendom’s finest modern writers, Flannery O’Connor. O’Connor is cited as one of McMurtry’s creative influences. I thought it a fitting gesture, an atheist collecting a Christian only to be purchased by a fellow-sojouner.