By Brian Nixon —

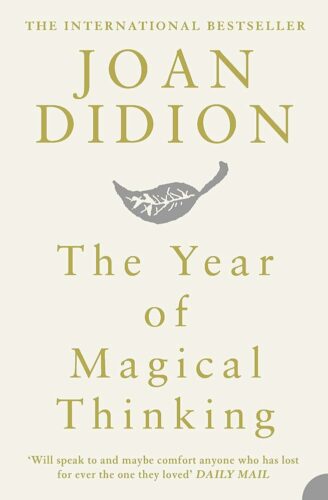

Though raised Episcopalian, author and journalist, Joan Didion, wrote little concerning her personal faith. Mostly she saw herself as agnostic and showed irritation with religious dabbling in politics. When her husband, John Dunne, a Catholic, died in 2003 she dealt with her sorrow by writing the Pulitzer-nominated and National Book Award winner The Year of Magical Thinking. In this work, Didion grapples with grief. Soon after, in 2005, her daughter, Quintana, died from complications from a fall, leading to pancreatitis. Didion deals with her sorrow by writing another book, Blue Nights.

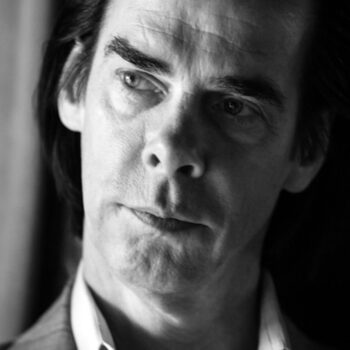

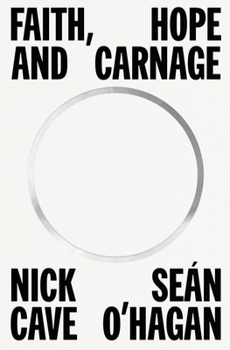

Compare this with Australian author and musician, Nick Cave. Like Didion, Cave lost two people in his family, sons Arthur (age 15) and Jethro (age 31). And like Didion, Cave dealt with his grief via creative means, composing the sublime album Ghosteen and co-writing the book Faith, Hope, and Carnage. Both are masterpieces on grief. And over the past several years Cave continues to contribute to his blog The Red Hand Files, where he helps people deal with pain—and a host of other topics.

I’m fascinated by how people deal with grief. Having experienced a fair share myself, burying a child, losing a father in a tragic accident, and family sickness, grief is no stranger. I, too, have tried to re-direct the grief through creative means, composing and writing. And though I was unable to write anything of a substantive nature after losing our son, Riley, I wrote a poem for him years after his death. The poem is entitled For Riley and the Angels. It found its way into my book Tilt: Finding Christ in Culture.

Here’s the thing: Pain is persuasive; it gets your attention. Furthermore, sorrow can be seductive; it can lull you towards despair. It’s as Irish author, C.S. Lewis writes in The Problem of Pain:

“Pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pains: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world….”

So, how did Didion and Cave deal with grief? Here’s some snapshots from their works.

Didion:

• “Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it.”

• “We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses, we also mourn…ourselves.”

• “Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life.”

• “I learned to find equal meaning in the repeated rituals of domestic life. Setting the table. Lighting the candles. Building the fire…”

Cave:

• “It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve. That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined. Grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love, and, like love, grief is non-negotiable.”

• “Hope is optimism with a broken heart.”

• “Vulnerability is essential to spiritual and creative growth. Finding enormous strength through vulnerability. You’re being open to whatever happens, including failure and shame. The two are connected.”

• “You have to operate, at least some of the time, in the world of mystery, beneath that great and terrifying cloud of artistic unknowing.”

• “And then comes the reassembled self, the self you have to put back together. You no longer have to devote time to finding out what you are, you are just free to be whatever you want to be, unimpeded by the incessant needs of others. You somehow grow into the fullness of your humanity…” As admirers of both Didion and Cave’s work, it’s good to connect with fellow sojourners of sorrow. And though Didion yearned to turn to God (but with little repose), Cave has been more successful (at least from what is reported) in developing personal faith. As Cave infers in his book, grappling with God helps the healing.

As admirers of both Didion and Cave’s work, it’s good to connect with fellow sojourners of sorrow. And though Didion yearned to turn to God (but with little repose), Cave has been more successful (at least from what is reported) in developing personal faith. As Cave infers in his book, grappling with God helps the healing.

Recently, Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, interviewed Cave on some of these themes, asking what Cave believes and how his beliefs shape his “values and actions.” Cave’s answers are fascinating and worth a listen.

To pay homage to Didion, I drove by her childhood home at night in Sacramento, taking a photo of the house, one she likened to a “cake.” I think the photo summarizes pain and sorrow well, giving a clue how to work through it.

As one can see in the photo, the atmosphere around the house is dark; so, too, is a life engulfed in pain, sorrow, or despair. Some of the leaves from the tree branches are gone, much like the energy and lifelessness one feels during sadness. But, in contrast, some trees are lightened, and the porch is illuminated, as are some rooms. There is light in the darkness.

And herein is a means to deal the grief: During sorrow, sadness, and despair—turn on the light. This can be the light of creativity—as Didion and Cave—demonstrate. Or maybe the light of helping others deal with the problem of pain, again, as Didion, Cave, and Lewis do with their works.

But more importantly, seek the light of God’s love. Allow, the Light of the World to bathe you in His illumination, creating enough radiance for you to walk the path and find your way home. Or put another way, as Didion suggests: Light a candle, and build a fire.