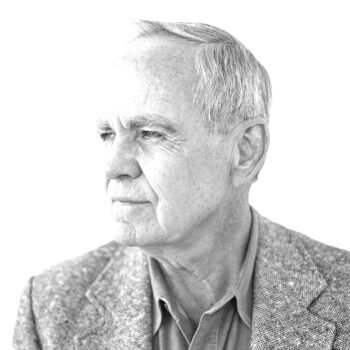

By Brian Nixon — With the news that Pulitzer-winning author, Cormac McCarthy, died at his

home on Tuesday, June 11 in Santa Fe at age 89, we revisit an article Brian Nixon wrote about McCarthy for ANS News, later adapted in Nixon’s book Tilt: Finding Christ in Culture.

__________________________

In Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer-winning novel The Road, a father and son leave on a journey in a post-apocalyptic world; the father trying to find wellbeing for his son, keeping him safe from hoards of human-eating people with only one bullet in his gun. It’s an amazing novel, really; one every father should read. It deserves the accolades bestowed upon it.

In a moment of inspiration, I, too, decide to take journey with my son. No, I’m not fighting human-eating people, nor do I have a one-bullet gun. But I am doing it for my wellbeing; a type of intellectual voyage full of Cormac McCarthy and time with my youngest child, Cailan.

To summarize the excursion: we took a driving tour around—what I call—the McCarthy loop. Beginning in Santa Fe we head down I-25 to El Paso, connecting with I-10, then to I-35 to San Marcos, Texas. There’s reason for all the stops, of course, all related to McCarthy.

But why choose to follow McCarthy around the Southwest?

Besides being one of the finest living writers working in the English language, McCarthy (b. 1933 in Providence, Rhode Island) is a writer of theological and philosophical weight, asking questions about evil, God, freedom, and suffering with amazing, if unsettling, insight. As one who studies theology, I am both fascinated and repelled by McCarthy’s stark prose and vision. McCarthy is a writer of profound nuances, mythical and real—all wrapped up in his almost Biblical prose.

Besides being one of the finest living writers working in the English language, McCarthy (b. 1933 in Providence, Rhode Island) is a writer of theological and philosophical weight, asking questions about evil, God, freedom, and suffering with amazing, if unsettling, insight. As one who studies theology, I am both fascinated and repelled by McCarthy’s stark prose and vision. McCarthy is a writer of profound nuances, mythical and real—all wrapped up in his almost Biblical prose.

Picking up on the theological themes manifest in McCarthy, the forthcoming book, Cormac McCarthy and the Signs of Sacrament by Harvard Divinity School professor, Matthew L. Potts, describes the interplay of Christian theology and McCarthy’s novels:

“In McCarthy’s novels, the human self is always dispossessed of itself, given over to harm, fate, and narrative. But this fundamental dispossession, this vulnerability to violence and signs, is also one uniquely expressed in and articulated by the Christian sacramental tradition.

“By reading McCarthy and this theology alongside postmodern accounts of action, identity, subjectivity, and narration, Potts demonstrates how McCarthy exploits Christian theology in order to locate the value of human acts and relations in a way that mimics the dispossessing movement of sacramental signs. This is not to claim McCarthy for theology, necessarily, but it is to assert that McCarthy generates his account of what human goodness might look like in the wake of metaphysical collapse through the explicit use of Christian theology.”

With fascinating ideas like these in mind, we jumped in our truck and began our journey in Santa Fe.

Why Santa Fe? Other than it being the city that Cormac McCarthy resides, it houses the Santa Fe Institute—the organization that blends science, literature, and a host of other disciplines under one roof; it’s an organization that McCarthy cares deeply about.

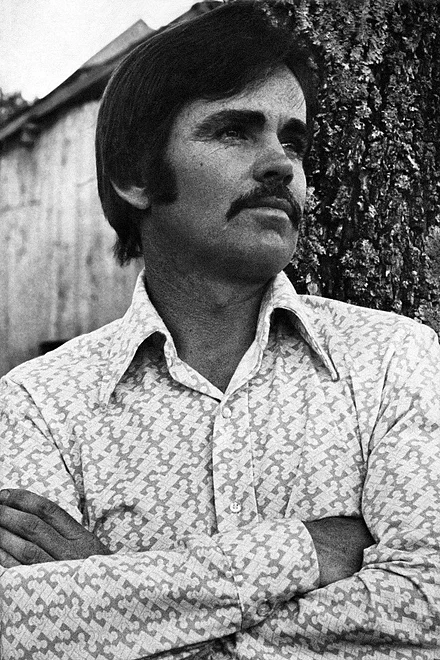

Upon a recent visit to the Santa Fe Institute I learned that Cormac had his hand in many of its decorative elements: the portrait of Isaac Newton hanging above the conference room fireplace (Cormac commissioned the artist) and the trimmings of another meeting room, resembling a pool hall. I was also shown the desk in the library where Cormac likes to read and write. It just so happened that the day I stopped by another Pulitzer-prize winning author, Sam Shepard, was sitting at the desk [1].

McCarthy writes about arriving at the Santa Fe Institute in a newsletter, a section entitled SFI@30: “The first MacArthur Fellowship meeting in Chicago was sort of like a television show. We were whisked away to a beautiful old house on the lake-shore in private limousines. There were just a handful of us and none of us really knew what the whole thing was about. Just that they were going to give us some money. We went down in the evening for cocktails and dinner and I made a bee-line for the physicists. Murray Gell-Mann and David Gross and John Schwartz and George Zweig and others. They included me in their group without question. Murray and I became friends and here I am.”

These friends McCarthy mentions are some of the founders of the Santa Fe Institute. And in Santa Fe McCarthy continually resides, keeping great company with these esteemed scientist.

McCarthy arrived in Santa Fe after living a few years in El Paso, Texas. It was in El Paso that McCarthy wrote some of his Western-inspired books—from Blood Meridian (considered by Harold Bloom to be the greatest modern Western American novel) to the beginning of his Border Trilogy novels: All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, and Cities of the Plain. Cormac moved to the Southwest after living in Tennessee, where he wrote his earlier Southern inspired novels.

Knowing this, El Paso was our next destination.

Cailan and I left Santa Fe on a Sunday. We drove down I-25 past the land of the outlaw, Billy the Kid (Lincoln County), Apache chief and fighter, Geronimo (Socorro and Sierra Counties), and a host of scientific marvels (The Very Large Array radio telescopes and the Space Station). There were road signs promoting the renovation of a 400-year old Catholic Church (McCarthy was raised Catholic). This region is very McCarthy-ish: science and theology meets the desolate west, with a tad of history and violence tossed in.

We arrived in El Paso shortly after lunch.

McCarthy lived on a street named Coffin Avenue (the number will remain anonymous for the sake of the current owners). It’s tucked in a small community adjacent to barren hills. If you drive to the end of Coffin Ave it stops at a small cliff, giving one a view of the area below. The street runs in an odd, off kilter trajectory. But it’s a nice, if unassuming, neighborhood. The El Paso house has recently been immortalized in the book, Cormac McCarthy’s House: Reading McCarthy Without Walls by Peter Josyph. When Cailan and I arrived it was a beautiful sunny day, about 75 degrees. A couple were walking a dog, others folks were doing yard work. Basically, it’s like any upper-middle class neighborhood in America. It just so happened that a particular house in the neighborhood had great American author who penned some masterpieces in its walls.

I snapped a couple of photos, thinking, “So this is where it happened.”

We drove through El Paso, connecting to I-10. You get a sense of the isolated area McCarthy wrote about in his Border Trilogy novels as you drive this portion of the freeway. Cactus interspersed with brush, treeless mountains in the distance. El Paso is a connector city to Juarez, Mexico. The area is a comparison of two cultures, of two languages, of two ways of life. These themes are prominent throughout the Border Trilogy books, particularly All The Pretty Horses and The Crossing and even No Country For Old Men, made into an Oscar-winning film.

After a stop in San Antonio (where the Briscoe Western Art Museum Book Club is studying Blood Meridian) to visit the Alamo, missions, and take in some art, we caught the I-35 and headed North to San Marcos.

The drive up the I-35 is like many American freeways: cities spotted along the way, all with strip malls and similar restaurants. The mountainous hills and brush seen on I-10 have turned into rolling hills, grass-lined fields, trees, and large vulture eagles.

Why stop in San Marcos?

If there is a Jerusalem to this McCarthy pilgrimage, San Marcos is it. The Wittliff Collections houses the McCarthy papers and manuscripts—the Holy Grail of McCarthy’s work. Housed in the Albert B. Lakek Library on the campus of the Texas State University, San Marco, the Wittliff collection has a host of esteemed Western writers, Sam Shepard, Larry McMurtchy, even Willie Nelson memorabilia. Many consider the acquisition of McCarthy’s papers as the great catch, helping put the collections on the collections map.

If there is a keeper of the Grail it is Katharine Salzmann. She is a marvelous person, but more on her in a moment.

Cailan and I park the truck in the garage. We walk to the library, heading to the 7th floor. As you enter the Wittliff section of the building cream-colored walls with wood trimming greet you. Two students sit at a desk. We say our greetings.

Cailan and I peruse the Austin Music Poster art exhibit, viewing the host of folks that have played the Austin region. I was pleased to see a Tom Waits poster among the dozens of poster art. We then walked through the Willie Nelson exhibit on display. Great memorabilia.

It must be said that nowhere in my mind did I think I’d be able to see the McCarthy archives. I didn’t make an appointment, nor did I think it was open to non-researches (I was a reader/researcher at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, so I know the drill).

Yet after buying a book of letters between Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark published by Texas State University and the Wittliff collections, called 2 Prospectors, I asked the lady about the archives and the amount of researches that come each year to study the McCarthy papers.

“Oh, you’d need to email Kate about this. She has all the information,” she says, handing me a card.

“Thank you,” I reply.

Pretty much as I figured, I thought.

As I concluded my time in the exhibit space, I notice two ladies with a man and woman in a room with various author photographs hung on a wall, including two of McCarthy. The four people were talking about comic books, of all things. As it turned out, they were wrapping up their discussion as I was looking at the J. Frank Dobie exhibit, a western writer who spent some time in New Mexico.

The folks in the room said their goodbye. The lady turned to me and asked me a question about the Shepard and Dark book I was holding. I turn. It was Kate. How did I know it was her? I saw the documentary about Sam Shepard’s quest to collect the letters between he and Johnny Dark. The documentary is named, Shepard and Dark. Kate had a cameo as Sam Shepard was meeting with the Wittliff to discuss his papers and letters between Johnny Dark and himself. I let Kate know as such.

She invited me in the room.

The other lady with Kate was the former director of archives, now retired. Together they asked why came. I told her my story, the Cormac McCarthy loop. They seemed fascinated by the journey. Then it happened. “Would you like to see some original McCarthy manuscripts?” Kate asked.

“You can do that?” I asked. Now a dumb question; she is the lead archivist.

“Of course.”

“I’d be honored.” I then tell her that my sister is an archivist in New York, who is currently working with Neil Simon’s family on his archives. We chat some. I tell them I was a reader/researcher at the Huntington, explaining some of their reading protocol I encountered in California.

“What manuscripts would you like to see,” Kate asks?

“If it’s not too much of a problem, can I see Blood Meridian and The Crossing?”

As Kate walks through a door, the former director talks about some of the writers in the collection, telling a few stories about them.

Kate walks in with a cart, two boxes and card catalogs.

She takes one box off the cart, opens it up—and shows us Blood Meridian.

“Do I need gloves?”

“No, but as a reader at the Huntington, you know to handle them.”

And handle them I do. I flip through the first few pages, asking questions about editing, the typewriter, and manuscript condition. It’s an amazing experience.

Next came The Crossing. In a similar fashion we repeat the process. I’m enthralled in the sequence of events.

As she’s putting away the manuscripts, Kate tells be about the Wittliff Collections [2]. Founded by writer, William Wittliff, in 1987, the collection’s main focus is on Southwest writers, poets, and photographers of notable importance. Kate tells me that Mr. Wittliff is the catalyst behind the collections, the main proponent and spokesperson for the esteemed collection.

Kate tells me about meeting Mr. McCarthy. He was kind, liking to talk about great movies. But spoke little about his books.

In my mind Kate is a sage, a keeper of scrolls and information of deep importance—manuscripts of profound impact. She was kind, informative, and very helpful—even if I didn’t make an appointment.

Even my son, Cailan, seemed to take in the process with care. Kate asked him a few questions about books.

In The Road, the father reminds his son that he must be the keeper of the fire, stating.

“You have to carry the fire.”

I don’t know how to.”

Yes, you do.”

Is the fire real? The fire?”

Yes it is.”

Where is it? I don’t know where it is.”

Yes you do. It’s inside you. It always was there. I can see it.”

There’s speculation as to what “the fire” is in McCarthy’s books (a theme touched upon in a few). Some say life, other say God. Both are probably right. For me at this time, however, the fire is great literature.

I felt like reciting this section to Cailan, but didn’t. Instead we sat and stood in the Wittliff Collections with big smiles on our faces. Great literature is like a fire. It must be kept alive, burning bright for future generations. I felt like I was doing my part.

I was pleased that the road I took involved my son in a quest to understand a little more about great literature, finding time spent with him was the greatest gift of all. And though I didn’t have a one-bullet gun, I did have one word: fire.