By Mark Ellis –

As improbable as it may seem in human terms, the father of the mastermind of the worst domestic terror act in American history found reconciliation with the father of one of his 171 victims, confirming once more that God can bring beauty from amidst the rubble and ashes.

One father, Bill McVeigh, raised an All-American boy who later turned into a monster seemingly beyond redemption. Another father, Bud Welch, raised a beautiful daughter who attended church daily and used her gift for languages to help others in her work as a translator.

On a beautiful, sunny, Wednesday morning, April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh pulled a rented Ryder truck packed with explosives into a loading area next to the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and set off a truck bomb that killed 171 people, including three unborn children.

The massive blast injured at least 680 others and destroyed a third of the nine-story, reinforced concrete and glass building. It also damaged 324 other buildings within a 16-block radius, shattered glass in 258 buildings and demolished 86 vehicles.

Until 9/11, the Oklahoma City bombing was the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of the U.S., and is still the deadliest episode of domestic terrorism in the country’s history.

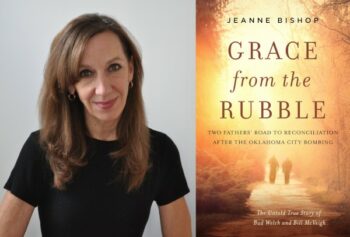

Author Jeanne Bishop did extensive research to craft a remarkable story of redemption in her book Grace from the Rubble: Two Fathers’ Road to Reconciliation after the Oklahoma City Bombing.

“I grew up in Oklahoma City and weaved my own memories of the place into the story,” she says. “It was such a shock because it was a city that believed in neighbor helping neighbor.”

When the blast hit, thousands of dollars of cash that had been stored within the building blew into the street. “More money was returned than was lost,” Bishop notes. “There was no looting. Everybody volunteered. The restaurants helped first responders. Faith and love of country came from those people that helped raise me. They epitomized what is so good about this country.”

The author is no stranger to tragedy herself. In 1990, her younger sister Nancy, 25, was murdered in her home along with her husband. “For six months no one knew who would kill this happy young couple. We were shocked to find it was a 16-year-old boy who lived a few blocks away.”

God prompted Bishop to reach out to the killer to find reconciliation and offer forgiveness. She went to visit him in prison and continues to visit with him. Her pain-filled, redemptive journey ultimately drew her to this story, which, in a sense, parallels her own.

Bud Welch’s daughter, Julie, nearly died at birth. She was born prematurely, a pound and a half, barely able to breathe. “Julie only had a 10 percent chance of living, but she survived,” Bishop says. “This was his only daughter, youngest child, his baby.”

When Julie went away to college, Bud called her every day to make sure she was all right. She was a genius at languages, fluent in five, and at the time of the attack worked as a Spanish interpreter on the first floor for the Social Security Administration in the Murrah building.

A young woman of deep faith, she got up an hour early every morning to attend mass. “She spent every single day in the presence of Christ,” Bishop says.

Her father, Bud, grew up on a dairy farm in Shawnee, Oklahoma, and was part of an Irish Catholic family with eight children. He ran a gas station in Oklahoma City at the time of the catastrophe. He had already lost a child shortly after childbirth and had gone through a divorce.

But this tragedy was worse. “Bud hated Timothy McVeigh and hoped a sniper would kill him on his way to court. For about a year, Bud was in the darkest place imaginable. He was just lost in his hate. He was going every day to the ruins of the Murrah Federal building. He was smoking four packs of cigarettes a day and drinking every night,” Bishop recounts.

Friends told him he was killing himself, but he said he didn’t care. “The sooner I die the sooner I go to heaven and see Julie,” he told them.

Bill McVeigh spent his entire life within a five-mile radius of Pendleton, New York, a rural area. Like Bud Welch, he also grew up on a farm, was Irish Catholic, went to Catholic schools through high school, and experienced a painful divorce that broke his heart.

He spent 40 years employed at an auto parts plant, working the furnace on the night shift so he could be there during the day to get Tim off to school.

His son, Timothy, was a completely normal kid growing up. “He wasn’t a good student or a bad student. He had never been in trouble at school or in trouble with the law,” Bishop discovered.

Due to poor job prospects in a sluggish economy, Tim joined the army. At Fort Benning, he met Terry Nichols and Michael Fortier, who became his co-conspirators in the bombing. “Both were anti-government, pro-militia. They had this anti-government hate that poisoned Tim McVeigh. Tim came back with PTSD, struggled to find a job and this anger fueled him, along with a love for weapons,” Bishop explains.

The conspirators’ motive behind the attack stemmed from anger at the federal government’s handling of the 1992 FBI standoff with Randy Weaver at Ruby Ridge as well as the Waco siege between the FBI and Branch Davidians that ended in the burning and shooting deaths of cult leader David Koresh and 75 others.

Tim decided to bomb a federal building as a response to the raids.

“Bill McVeigh was dumbstruck, horrified when he got the news. He was so devastated that a child of his could cause such hurt to other people and he cooperated fully with the FBI,” Bishop says.

As Bud Welch stewed in his anger, he began to wonder why McVeigh carried out such a horrific act. When he discovered that Tim’s motive was retaliation for Waco and Ruby Ridge, he also saw that his own desire for revenge would keep the cycle going.

God moved his heart to seek reconciliation and forgiveness, and the progression of retaliation and revenge would end with him.

He wanted to meet with Timothy McVeigh, but couldn’t. “So he decided to find Tim’s father,” Bishop explains.

Welch sought help from a Catholic nun, Sister Rosalind, in his search for Bill McVeigh. Sister Roz, a counselor at Attica prison, also worked at a halfway house for inmates recently released from prison. “It’s a job so dangerous her colleague, Sister Donna, was murdered there.”

In the book, Bishop describes their tender, emotional meeting for the first time. “Both of them were terrified. It was hard for Bud to walk through the door of this home where his daughter’s murderer had lived. Bill was very nervous because he knew his son had done this terrible thing to Bud’s daughter,” she says.

To avoid spoiling the book, the details of their remarkable meeting will be held back.

Later, Ed Bradley of 60 minutes interviewed Welch and asked him what he would want to say to Timothy McVeigh before his scheduled execution.

Bud said, “I would want to sit down with Tim and show him a picture of Julie, my daughter, and say, ‘If you grew up in the same neighborhood together and were the same age, you probably would have been buddies. I would want to put a human face on one of the 168 that he killed. And I want him to ask for forgiveness before he dies.”

Bradley seemed stunned by his answer, the fact that Welch didn’t want revenge.

“Bud wanted this killer to understand something of the enormity of what he took,” Bishop explains. “We are promised in Psalm 23 that we are walking through this valley of the shadow of death, but God is with us.

“We are not alone and evil will never had the last word.”