By Mark Ellis —

He was the only man on his landing craft to come ashore at Omaha Beach with no “visible” weapons to protect himself. But that didn’t stop this chaplain from being the first man out of his boat.

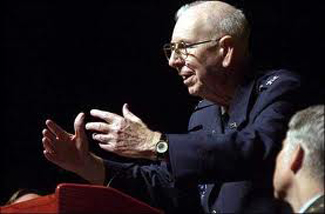

“I had the sword of the Spirit,” said Lt. Col. George Russell Barber, USAF (Ret.), who started his career with the horse cavalry along the Mexican border before World War II. “We were all afraid,” he explained, as the men came ashore June 6, 1944, amidst a hail of bullets and fiery explosions. “If a man says he’s not afraid, he’s lying—but we had our faith.”

My last visit with Colonel Barber was six months before his passing on December 17, 2004 at age 90. He wanted to attend the dedication of the World War II Memorial in Washington D.C. in 2004, but health concerns kept him away. Although the strength in his legs was failing, his mind was sharp and his grip still strong.

He served his country in four wars, and one of his most powerful memories was the D-Day invasion on Omaha Beach. “On the Sunday before D-Day I held services on 11 different ships in Weymouth Harbor for thousands and thousands of soldiers,” he said. “I gave away a lot of pocket Gideon’s Bibles–there are no atheists in foxholes.”

On the fateful morning of the invasion, he went over the side of his ship on a rope ladder into a flat-bottomed landing craft that held 30 soldiers.

“When we hit the shore they let down the ramp I stood in front and led my men off,” Chaplain Barber recalled. “They were shooting at us all around.”

To the right, Barber witnessed a horrible sight. “Just before we landed I saw a landing ship hit a

mine,” he said. “It blew up and killed all 30 men. They were floating in the water and on the beach.”

Without hesitation, Barber rushed to the sides of the wounded. “I talked to as many as I could and prayed with them. I said, ‘Trust in God.’” As men died in his arms he recited John 14: “Do not let your hearts be troubled. Trust in God; trust also in me. In my Father’s house are many mansions…”

“Men were being killed all around me,” Barber said. “We were all trying to dodge the bullets. Thank God I wasn’t hit.” Miraculously, none of the four chaplains landing on the Normandy Beaches that day were killed, according to Barber.

If they survived the barrage of hostile fire, the next challenge for Barber and his men was to climb over steep cliffs just beyond the shore. “I couldn’t get over the 100 foot cliff so I had to dig my own foxhole that night on the beach,” he noted. “I prayed as if everything depended on the Lord, and I dug as if everything depended on me.”

“The Lord and me got that foxhole pretty deep.”

Unable to sleep, Barber crouched in his crude shelter amidst the storm of battle. Through the night, he stared up at a frightening display. “I watched the sky lit up by tracer bullets. Every fifth bullet is a tracer bullet, so you can see it go up and come down.”

“The next morning I got over that cliff and I met Ernie Pyle, the famous war correspondent for Stars and Stripes,” Barber recalled. “We split a can of Spam together.” Later that day, the two men walked Omaha Beach together, past the bodies of over 1500 who had fallen in battle. “We saw all the carnage and death and destruction.”

Pyle wrote his own account of their walk together. “The wreckage was vast and startling,” he wrote. “In the water floated empty life rafts and soldiers’ packs and ration boxes…But there is another and more human litter. It extends in a thin little line, just like a high water mark, for miles along the beach.”

“Here are socks and shoe polish, sewing kits, diaries, Bibles and hand grenades. Here are toothbrushes and razors, and snapshots of families back home staring up at you from the sand.”

Then Correspondent Pyle did something on their walk the chaplain remembered vividly. He bent over and picked up a pocket-sized Gideon’s Bible that was next to a fallen soldier. “I picked up a pocket Bible with a soldier’s name in it, and put it in my jacket,” Pyle wrote. “I carried it for a mile or so and then put it back down on the beach. I don’t know why I picked it up, or why I put it back down.”

“I can’t prove it,” Chaplain Barber said, “but I probably gave that soldier that Bible only two days before that.” Less than one year later, Pyle lost his own life near Okinawa when a Japanese sniper killed him as he covered the war in the Pacific.

Chaplain Barber also survived the Battle of the Bulge, and was at the Remagen Bridge spanning the Rhine River immediately before it collapsed. Later, he and his men visited a concentration camp at Nordhausen, Germany. Before Allied troops arrived, Germans crowded 200 Jewish men into a building and set it afire. No one survived the flames. “War is ugly. War is hell,” Barber said.

After the war, Chaplain Barber met two members of the Polish underground while he stayed at a hotel in Germany. One day, the three men decided they would climb one of the highest mountains in Germany. “It was a windy and snowy day,” Barber noted. They pulled themselves up some of the steep faces using a steel cable someone had left behind.

As a bitterly cold wind stung their faces, they reached the summit, and Barber found something surprising. “There on top of one of the highest mountains in Germany we found a large white cross,” he says. The wind at that elevation made it hard for the three men to keep their balance. “We held on to the cross as we looked over the edge.

“What better thing to hold on to in the storms of life than the cross of Christ,” he said.