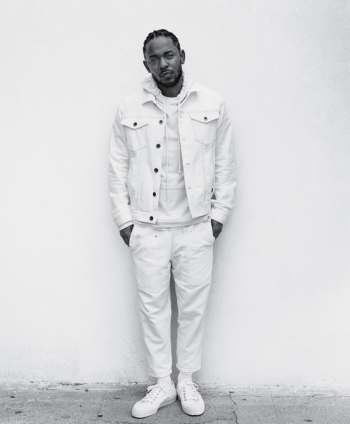

Left dazed and reeling with fury, Kendrick Lamar was in a Food 4 Less parking lot after his buddy had just been shot and killed. Rage for revenge burned inside, but so did a gripping sense of horror at the evil in this world.

Seeing him in turmoil, a friend’s grandmother approached and talked to Kendrick about God, and the teenager accepted Jesus into his heart.

“One of my homeboys got smoked,” Lamar told the New York Times. “She had seen that we weren’t right in the head. That was her being an angel for us.” He got baptized a decade later.

Today, the seven-time Grammy winner makes frequent reference to God’s salvation and grace, as well as temptation and fear of judgment in his songs. While the rank and file of the church eschews him for his profanity and descriptions of sexual sin in other songs, his secular audience has no doubt about his faith.

“I’m the closest thing to a preacher that they have,” says Lamar, 31. But he adds, “My word will never be as strong as God’s word. All I am is just a vessel, doing his work.”

Vassar College professor of music Kiese Laymon calls him a “prophetic witness.” Revolt online magazine says Lamar “wears his faith, spirituality, and religious beliefs on his sleeve.” He doesn’t drink, smoke, use drugs or womanize.

Lamar is part of the bridge forming between secular and Christian hip hop. While Lecrae moves toward the secular side, Lamar and a host of other artists are pulling away from unbridled hedonism and exploring salvation themes. (Chance the Rapper, Snoop Dogg, Kanye West and even Drake also include songs that talk unashamedly about God and Jesus in their repertoire.)

Lamar grew up in Compton, Calif. His father belonged to the Gangster Disciples gang. Little Kendrick witnessed his first murder at 5 and his second at 8. His parents didn’t teach him about God, but his grandmother instilled him with Bible knowledge.

Growing up on welfare, living in Section 8 housing, the youngster worried that he would succumb to the debasing poverty, drug-trafficking, violence and hopelessness of the hood, even though he was a straight-A student.

Growing up on welfare, living in Section 8 housing, the youngster worried that he would succumb to the debasing poverty, drug-trafficking, violence and hopelessness of the hood, even though he was a straight-A student.

At just 16, he signed for Top Dawg Entertainment, based in Carson, Calif., under the stage name K-Dot. After opening for prominent artists and working with Snoop Dogg, Lamar broke through on his own with his second album Good Kid, MAAD City, which hit Billboard’s #2 in its first week in 2012. In it, he depicts vividly the urban fiendishness of the hood.

He opens the album with these words: Lord God, I come to you a sinner, and I humbly repent for my sins. I believe that Jesus is Lord. I believe that you raised Him from the dead. I will ask that Jesus will come into my life and be my Lord and Savior. I receive Jesus to take control of my life that I may live for Him from this day forth. Thank you, Lord Jesus, for saving me with your precious blood. In Jesus’ name, Amen.

He followed up in 2015 with To Pimp a Butterfly, which went certified platinum and won a Grammy for best rap album of the year. Then in 2017 he came out with Damn, which fathoms the loss of faith in the light of a volatile world of malfunction.

He followed up in 2015 with To Pimp a Butterfly, which went certified platinum and won a Grammy for best rap album of the year. Then in 2017 he came out with Damn, which fathoms the loss of faith in the light of a volatile world of malfunction.

While Lamar’s music is pioneering, it’s his vocal inflections and lyrical substance that earn him widespread respect. For Damn, he won the first-ever Pulitzer Prize not given to jazz or classical music. Former President Obama singled out Lamar as one of his favorite rappers. He’s called King Kendrick.

On Damn, an apparent endorsement of the Hebrew Israelite movement, an aberrant group with claims blacks in America are actually God’s chosen people from Israel, elicited a response from Christian rapper Flame, who in “Absolute Truth” exposes their flawed exegesis.

“A lot of people fall for it,” Flame said on the radio program of Vocab Malone. “It feels good. It puffs up your pride, the ethnocentrism.”

Damn is less uplifting than his earlier albums. By plumbing the depths of discouragement, Lamar is encouraging his listeners that platitudes should be discarded and that it’s okay to be real and raw before God.

But it’s not his latest, darker album that has youth pastors red-flagging Lamar to their kids. It’s his ample use of profanity — and explicit description of sex. Such is normal fare for worldly hip hop, but not the Christian knockoff that once was called “Holy Hip Hop.”

There isn’t much that can be said in favor of the inappropriate language. But the raunchy romps are arguably narratives that show kids in the hood the consequences of sin, the need of grace and the value of repentance. Lamar is not aiming to edify saints but rescue sinners, and the song is not a reveling in sin but serving as a parable.

This is what Daniel White Hodge calls in his book Hip Hop’s Hostile Gospel a combination of “the sacred, profane, and secular in a tightly woven social knot which creates a type of nitty-gritty hermeneutic in which his audience members are able to relate and engage.”

This is what Daniel White Hodge calls in his book Hip Hop’s Hostile Gospel a combination of “the sacred, profane, and secular in a tightly woven social knot which creates a type of nitty-gritty hermeneutic in which his audience members are able to relate and engage.”

Monica Miller, associate professor at Lehigh University, says in Christianity Today, “It’s not a contradiction, it’s life. Hip-hop is OK with complexity. It doesn’t have to be either/or.”

Among Christian listeners who are supportive of Lamar’s floundering in faith there is CHH legend Lecrae. When Lecrae first heard Lamar’s 2009 EP called “Faith,” he immediately called him and struck up a relationship with him.

The song “touched me and I reached out to him like, ‘Hey, can I talk to you about it?'” Lecrae noted in Buzzfeed. “We started talking and that’s really how our relationship began. In this industry, a lot of people shake hands and high-five each other, but there’s not a lot of genuine conversation about the deeper things in life.

“When you’re struggling with your girl or your mom is sick, it’s rare that you find someone that actually wants to talk with you on a real level. So being able to connect with him on spiritual matters is definitely something that I value and appreciate.”

One line from “Faith”: But what I do know, is that He’s real and He lives forever / So the next time you feel like your world’s about to end / I hope you studied because He’s testing your faith again.

Lamar is not Sunday school material. As Titus Willis argues, Lamar is all about “the trials and travails of growing up as a minority in a disadvantaged neighborhood.”

Since finding fame and fortune, Lamar has moved back to Compton where he lives in a modest condo. The money doesn’t hold sway over him. His ultimate aim is to bring hope to those who have none

“What gives me inspiration is giving thought and game to people who don’t have it,” Lamar says. “We’re putting in the real work with these kids and these ex-convicts.”

“What gives me inspiration is giving thought and game to people who don’t have it,” Lamar says. “We’re putting in the real work with these kids and these ex-convicts.”

If you want to know more about a personal relationship with God, go here

Ryan Zepeda studies at the Lighthouse Christian Academy in Los Angeles.

Read about other Christian hip hop artists by clicking: 1K Phew – Aaron Cole – Ada Betsabé –Andy Mineo – Benjamin Broadway — Bizzle – Canon – Cass – Datin – Flame – Gawvi – HeeSun Lee – Jackie Hill-Perry – Jarry Manna — JGivens – Joey Vantes — John Givez – KB – Lecrae – Lil T Tyler Brasel– MC Jin – NF – nobigdyl. – Propaganda – Ray Emmanuel – Ruslan – Sevin – S.O. — Social Club Misfits – Steven Malcolm – Tedashii – Tobe Nwigwe – Trip Lee – Wande Isola – WhatUpRG — YB

And secular rappers who have come to Christ (at least to some degree): Chance the Rapper – Kanye West – Kendrick Lamar – No Malice — Snoop Dogg

And an overview article about the state of affairs in CHH: Christian Hip Hop in Controversy.

Comments are closed.