When Daryl Davis held the American flag for his Cub Scouts troop in a march from Lexington to Concord to commemorate Paul Revere’s ride, he swelled with pride as an American.

What the 10-year-old never expected was the bottles, soda cans and rocks hurled at him. As one of only two black children in the area in 1968, he was being targeted by some of the whites in the crowd.

“This was the first time I ever experienced anything like this,” he recalled. “I did not understand.” Scout leaders huddled over him with their bodies and escorted him out of danger. “I kept asking, ‘Why? Why? What had I done wrong?’”

But the Scout leaders said nothing, and it wasn’t until his parents were cleaning and patching up his bruises and scratches that he began to learn about the ugly underbelly of America.

“For the first time in my life, my parents sat me down and explained to me what racism was. I had absolutely no idea what they were talking about,” he recalls. “It was inconceivable to me that somebody who had no idea who I was, who had never laid eyes on me, who had never spoken to me, would want to inflict pain on me for no other reason that the color of my skin. So I did not believe my parents.”

“For the first time in my life, my parents sat me down and explained to me what racism was. I had absolutely no idea what they were talking about,” he recalls. “It was inconceivable to me that somebody who had no idea who I was, who had never laid eyes on me, who had never spoken to me, would want to inflict pain on me for no other reason that the color of my skin. So I did not believe my parents.”

As he grew up, he was faced with more racism, but he never understood it: “How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?” The question haunted him, and, in his quest for the answer as he grew up, he read books about white supremacy, black supremacy and many others. None of these books offered an explanation.

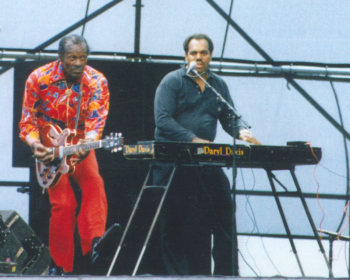

So as an adult, he struck upon the idea of asking Ku Klux Klan members why they hated him. By now, he had become a professional R&B and blues musician and had played with the likes of Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, B. B. King and Bruce Hornsby. He was also a fervent Christian. He proposed to write a book about hate in his spare time.

So as an adult, he struck upon the idea of asking Ku Klux Klan members why they hated him. By now, he had become a professional R&B and blues musician and had played with the likes of Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, B. B. King and Bruce Hornsby. He was also a fervent Christian. He proposed to write a book about hate in his spare time.

In 1983, he scheduled his first interview with Roger Kelly, the Grand Dragon for Maryland. Daryl neglected to mention that he was black, so when Kelly and an armed guard showed up, they froze.

But Daryl welcomed him warmly and encouraged him to talk. The spoke calmly and compared ideas. Tempers didn’t flare. They disagreed but treated each other with cordiality and respect.

The first conversation led to a second and then to a third. Soon they were friends. The armed guard dropped out of the picture. They shared lunches and dinners. Kelly invited Daryl to a KKK rally, and he attended. He listened to speeches and watched them burn crosses. Kelly went to watch Daryl play boogie-woogie on the keyboard.

Eventually, Kelly renounced his racism and resigned from the KKK. Daryl’s quest to comprehend racism had converted a racist.

“Respect was the key,” says Daryl, now 60. “Because I was willing to listen and he was willing to listen to me, he ended up leaving the Klan.”

Eventually, Daryl learned where racism comes from: “Ignorance breeds fear, and if we do not keep that fear in check, it breeds hatred,” he says. “And it we do not keep the hatred in check, that hatred in turn will breed destruction.

“It’s a wonderful thing when you see a light bulb pop on in their heads or they call you and tell you they are quitting,” he adds. “I never set out to convert anyone in the Klan. I just set out to get an answer to my question: ‘How can you hate me when you don’t even know me.’ I simply gave them a chance to get to know me and treat them the way I want to be treated.”

Today, Daryl has rescued more than 200 Klansmen from their robes. His tactic of making friends with his haters with the love of Christ and calm conversation has helped them see the light.

“I am a musician, not a psychologist or a sociologist,” he says. “If I can do that, anybody can do that. Take the time to sit down and talk with your adversaries. You will learn something from them, and they will learn something from you. When two enemies are talking, they’re not fighting. It’s when the talking ceases that the ground becomes fertile for violence, so keep the conversation going.”

Kiera Sivrican studies at the Lighthouse Christian Academy in the Los Angeles area.

Comments are closed.