By Mark Ellis –

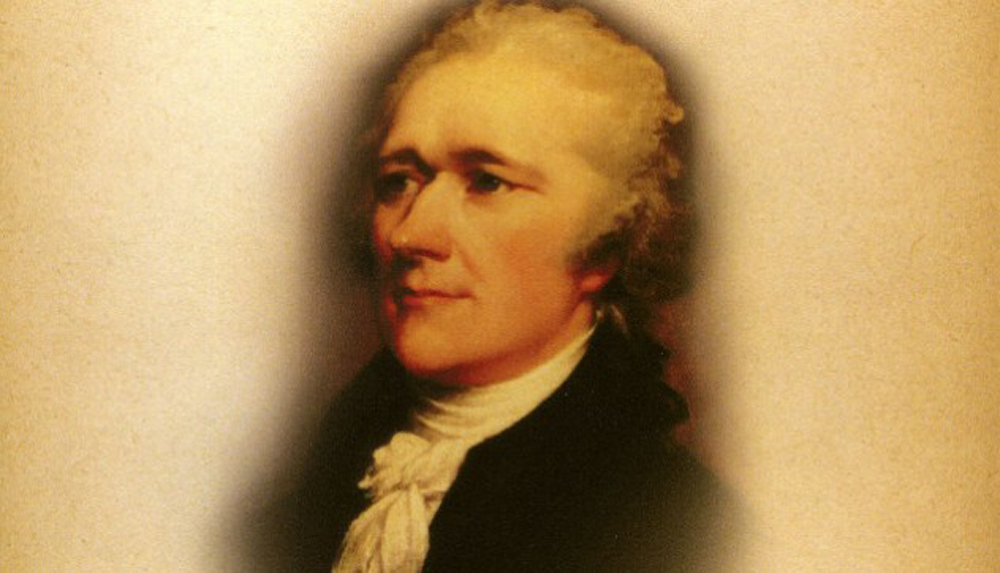

The smash hit musical Hamilton about America’s founding father features high-tempo rapping and racially diverse casting of the founders, with black and Hispanic performers in key roles including the role of Alexander Hamilton himself.

It was inspired by Ron Chernow’s massive and elegant biography about the colonial protean genius, who largely created the foundations of the federal government single-handedly and became the leading light of the Federalist party.

But it probably won’t surprise anyone to learn that one missing piece in the Broadway musical was any reference to Hamilton’s faith in Jesus Christ.

But it probably won’t surprise anyone to learn that one missing piece in the Broadway musical was any reference to Hamilton’s faith in Jesus Christ.

Admittedly, the devotion of his early years seemed to be lost during midlife, when some might describe him as backslidden. But abundant evidence exists that a fervent faith emerged in the final chapters of his dramatic life, albeit cut short by his tragic demise at age 49.

Growing up on the island of Nevis in the West Indies, Hamilton was tutored by a Jewish schoolmistress and learned to recite the Ten Commandments in the original Hebrew.

Between the age of 10 and 14, he (along with his brother) endured horrible personal tragedies, as recounted by Chernow:

“Their father had vanished, their mother had died, their cousin and supposed protector had committed bloody suicide, and their aunt, uncle, and grandmother had all died…Their short lives had been overshadowed by a stupefying sequence of bankruptcies, marital separations, deaths, scandals, and disinheritance.”

When Hamilton was 17, a massive hurricane hit the island and Hamilton penned a letter about the experience. He shared the letter with his pastor, Hugh Knox, who happened to be a part-time journalist, and Knox insisted the letter should be published in the newspaper. Here is an excerpt from Hamilton’s vivid description of the storm:

“It seemed as if a total dissolution of nature was taking place. The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about it in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed, were sufficient to strike astonishment in the angels.”

Then Hamilton shifted into a sermon-like exhortation to his fellow man:

“Where now, oh! vile worm, is all thy boasted fortitude and resolution? What is become of thine arrogance and self sufficiency?…Death comes rushing on in triumph, veiled in a mantle of tenfold darkness. His unrelenting scythe, pointed and ready for the stroke…See thy wretched helpless state and learn to know thyself…Despise thyself and adore thy God…O ye who revel in affluence see the afflictions of humanity and bestow your superfluity to ease them…Succor the miserable and lay up a treasure in heaven.”

Hamilton’s remarkable letter caught the attention of influential people on the island, who established a fund to send the promising young man to North America to be educated.

He landed at a prep school in New York and later was admitted to King’s College (which became Columbia University). A wealthy attorney named Elias Boudinot, who owned copper and sulfur mines, and later became president of the Continental Congress and the first president of the American Bible Society, took Hamilton under wing.

Boudinot and his family undoubtedly exerted a strong Christian influence on Hamilton. Moreover, Christianity saturated King’s College at the time. Morning chapel was obligatory before breakfast and students were required to attend church twice on Sunday.

One of Hamilton’s college friends, Robert Troup, testified to his piety. He “was attentive to public worship, and in the habit of praying on his knees night and morning…. I have often been powerfully affected by the fervor and eloquence of his prayers… He had read many of the polemical writers on religious subjects and he was a zealous believer in the fundamental doctrines of Christianity.

“I confess that the arguments, with which he was accustomed to justify his belief, have tended in no small degree to confirm my own faith in revealed religion,” Troup noted later.

The dramatic events surrounding the American Revolution soon overtook Hamilton, who surprised those around him by being as adept with a musket as he was with a pen. He devoured books on military strategy and arrived at the conclusion that unconventional warfare could beat the British.

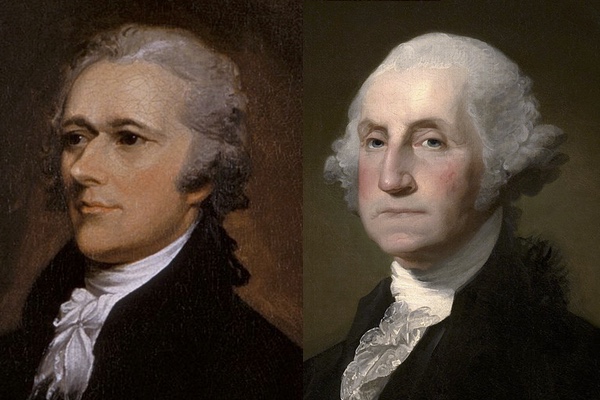

He came to the attention of several military leaders and on January 20, 1777, General Washington sent a note to Hamilton personally inviting him to join his staff as an aide-de-camp.

The relationship that soon developed between Washington and Hamilton was enormously “consequential in early American history,” Chernow notes. “Washington possessed the outstanding judgment, sterling character, and clear sense of purpose needed to guide his sometimes wayward protégé; he saw that the volatile Hamilton needed a steadying hand.

“Hamilton, in turn, contributed philosophical depth, administrative expertise, and comprehensive policy knowledge that nobody in Washington’s ambit ever matched…As a team, they were unbeatable and far more than the sum of their parts.”

Following the war, as the new nation’s first treasury secretary, he reached the apex of power and influence, but was not without controversy as he pushed for the creation of a national bank and national assumption of debts incurred by the states during the Revolution, among other nation-building initiatives.

“His vigorous reign had also made him the enfant terrible of the early republic, and a substantial minority of the country was mobilized against him,” Chernow notes. “This should have made him especially watchful of his reputation. Instead, in one of history’s most mystifying cases of bad judgment, he entered into a sordid affair with a married woman named Maria Reynolds that, if it did not blacken his name forever, certainly sullied it.”

Like King David, Hamilton paid a price for his sin and its aftermath undoubtedly led to his spiritual renewal.

Hamilton was horrified by the excesses of the French Revolution and wrote several essays critical of the efforts of the French to overthrow the Christian religion as robbing “mankind of its best consolations and most animating hopes, and to make a gloomy desert of the universe.”

“The praise of a civilized world is justly due to Christianity,” he noted.

Hamilton thought Christianity formed the basis of all law and morality and “the world would be a hellish place without it,” Chernow observed.

In 1802, Alexander and his wife, Eliza, purchased a country home they called The Grange, which allowed Hamilton to spend more time with his children. On Sunday mornings they gathered in the garden to sing hymns and Hamilton read the Bible aloud to his family. He also spoke to his wife about his desire to build a chapel on the property.

“It is striking how religion preoccupied Hamilton during his final years,” Chernow noted in his book.

When he became head of the new army following the Revolution, he asked Congress to hire a chaplain for each brigade so that soldiers could worship.

He was the driving force behind an effort to form the Christian Constitutional Society. In an 1802 letter to co-founder James Bayard, he said its object is first: “The support of the Christian religion. Second: The support of the United States.”

“I have carefully examined the evidences of the Christian religion,” he told one friend, “and if I was sitting as a juror upon its authenticity I would unhesitatingly give my verdict in its favor.”

To his wife Eliza he said about Christianity: “I have studied it and I can prove its truth as clearly as any proposition ever submitted to the mind of man.”

Sadly, Hamilton was mortally wounded in a duel with the sitting vice-president of the United States, Aaron Burr, in 1804.

On his deathbed, Hamilton asked to receive communion from Rev. Benjamin Moore, the rector of Trinity Church, the Episcopal bishop of New York, and the president of Columbia College. Shockingly, Rev. Moore refused, because he hated the practice of dueling and because Hamilton had not been a regular churchgoer.

In misery and despair, Hamilton turned to a friend, Rev. John M. Mason, the pastor of Scotch Presbyterian Church. Astonishingly, he also declined the request, saying his church had a principle “never to administer the Lord’s Supper privately to any person under any circumstances.”

Then Dr. Mason explained that the Lord’s Supper is not a requirement for salvation and he clearly communicated God’s plan of salvation to the dying man. Hamilton said he had not requested the Lord’s Supper as a means of obtaining heaven, and then testified:

“I am a sinner. I have a tender reliance on the mercy of the Almighty, through the merits of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

Some time later, Rev. Moore returned to Hamilton’s bed having had a change of heart and administered communion to the fading patriot. Hamilton told him he held no malice toward Burr, was dying in peace, and that he was reconciled to God.

“Then at 2:00 pm, on Thursday, July 12, 1804, 31 hours after the duel, 49-year-old Alexander Hamilton died gently, quietly, almost noiselessly.”

After his passing, Eliza discovered a hymn and a letter he wrote for her on the morning before the duel.

At the end he instructed: “Fly to the bosom of your God and be comforted. With my last idea, I shall cherish the sweet hope of meeting you in a better world. Adieu best of wives and best of women. Embrace all my darling children for me. Ever yours, AH”

If you want to more about a personal relationship with God, go here