By Mark Ellis

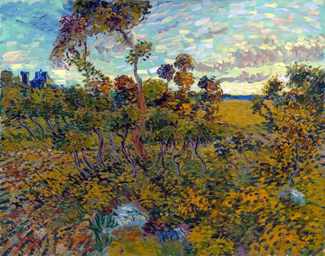

The unsigned painting lay hidden in the darkness of a Norwegian attic for close to a century. But now the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam hails ‘Sunset at Montmajour’ as an authentic product of the celebrated Dutch artist and a momentous find.

Norwegian industrialist Christian Mustad bought the painting in 1908 from a Paris art dealer, but was later embarrassed when an art expert declared it a fake, partly because ‘Sunset’ was unsigned.

“This guy was so humiliated, he wrapped it up in a blanket and put it in his attic,” says William Havlicek, Ph.D., author of “Van Gogh’s Untold Journey” (Creative Storytellers). “He thought he had been fooled.”

It lay in the gloom of the dust-filled attic until 1991, when the painting’s new owners contacted the Van Gogh Museum for an opinion. Experts rejected it once more, but “this was before new technology was developed,” Havlicek notes.

More recently, engineering professors at Rice and Cornell universities developed a signal-processing algorithm that automatically counts the thread density in an artist’s canvas from X-rays. “It’s a genetic profile that is like a fingerprint, it’s so accurate,” Havlicek says.

More recently, engineering professors at Rice and Cornell universities developed a signal-processing algorithm that automatically counts the thread density in an artist’s canvas from X-rays. “It’s a genetic profile that is like a fingerprint, it’s so accurate,” Havlicek says.

Based on the new technology and other convincing evidence, the Van Gogh museum declared ‘Sunset’ genuine and had a dramatic unveiling on September 9th.

Havlicek says a letter Vincent wrote to his brother Theo the day after the painting was finished offers clues to its authenticity.

On July 5th, 1888, Vincent wrote: “Yesterday, at sunset, I was on a stony heath, where very small, twisted oaks grow, in the background a ruin on the hill, and wheat fields in the valley. It was romantic, it couldn’t be more so, à la Monticelli, the sun was pouring its very yellow rays over the bushes and the ground, absolutely a shower of gold. And all the lines were beautiful; the whole scene had charming nobility.”

In the same letter, he suggests why he never signed the beautiful landscape: “I brought back a study of it too, but it was well below what I’d

wished to do.”

“Van Gogh would often put a painting aside and rework it,” Havlicek notes. “He struggled with it in a way that is not fully resolved, so it makes it very charming. It gives an insight into Van Gogh that you don’t find with a really finished work.”

From evidence supplied in the letters, Havlicek says the painter battled with loneliness at the time he painted ‘Sunset.’ Van Gogh lived alone in southern France for seven months and hoped fellow artists Gauguin and Bonnard would visit him, but that didn’t happen until several months later.

“Gauguin finally came and they had a lot of deeply theological conversations,” Havlicek says.

Many don’t realize van Gogh’s father and grandfather were pastors and Vincent nurtured strong faith himself. In his early twenties, he wanted to study theology, but failed his entrance exam for seminary. Instead, he served as a missionary to coal miners in the Borinage district of Belgium.

Havlicek spent 15 years researching and studying more than 900 of van Gogh’s letters. His enlightening book dispels many of the myths that surround the painter’s turbulent life. “Vincent’s letters portray a very different story than the popular tale of the mad artist who cuts off his ear,” Havlicek notes.

Numerous letters reveal the painter’s strong Christian identification. “Many of his religious letters were held back and only released in the last five or six years,” Havlicek says.

While some art critics believe van Gogh lost his faith in 1885, the year he was driven out of his family home, Havlicek disagrees. “I don’t

think he lost his faith, but I think he lost his faith in the church.”

Indeed, many of van Gogh’s most Christ-oriented paintings were completed in the last three years of his life, in 1888-1890. “Van Gogh’s interest in the Gospel is very profound,” Havlicek says. His paintings, The Good Samaritan, The Raising of Lazarus, Pieta, The Sower, The Sheaf Binder (or harvester) all display Christ-centered themes.

“He loved the idea of resurrection,” Havlicek notes. “It is funny that Van Gogh was listening to cicadas that were in the trees when he was working on this painting,” he says.

The cicada lifecycle resembles a type of resurrection. The cicada larvae remains suspended until it dries in the sun and its exterior hardens. Then it falls to the ground and is buried in the soil. It may spend several years underground until, one day in early summer it emerges, sheds its outer body shell, and flies away.

“They go underground and then they come up,” Havlicek observes. “This painting was put essentially underground – in an attic – for close to 100 years.”

In North America, cicadas on a 17-year cycle emerged in the summer of 2013. “This is the year of the cicada. It’s ironic that the year of the cicada should be the year the painting resurfaces.”

Comments are closed.