A knucklebone claimed to be of John the Baptist has been dated as first century AD by Oxford researchers. The new

dating evidence supports claims that bones found under a church floor in Bulgaria may be of the leading prophet and relative of Jesus Christ as described in the Bible.

The research by the Oxford University team will be explored in a documentary ‘Head of John the Baptist’ to be aired in the UK on National Geographic Channel on Sunday 17 June.

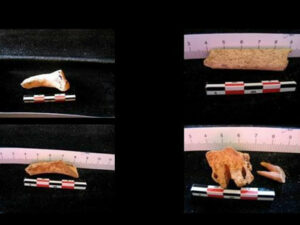

A team from the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at Oxford University dated a knucklebone from the right hand. The researchers were surprised when they discovered the very early age of the remains adding, however, that dating evidence alone cannot prove the bones to be of John the Baptist.

The bones were originally discovered in 2010 by archaeologist Kazimir Popkonstantinov, excavating under an ancient church on an island in Bulgaria known as Sveti Ivan, which translates into English as St John. The knucklebone was one of six human bones, including a tooth and the face part of a cranium, found in small marble sarcophagus under the floor near the altar. Three animal bones were also inside the sarcophagus. Oxford professors Thomas Higham and Christopher Ramsey attempted to radiocarbon date four human bones, but only one of them contained a sufficient amount of collagen to be dated successfully.

Professor Higham said: ‘We were surprised when the radiocarbon dating produced this very early age. We had suspected that the bones may have been more recent than this, perhaps from the third or fourth centuries. However, the result from the metacarpal hand bone is clearly consistent with someone who lived in the early first century AD. Whether that person is John the Baptist is a question that we cannot yet definitely answer and probably never will.’

Former Oxford student Dr Hannes Schroeder and Professor Eske Willerslev, both from the University of Copenhagen, also reconstructed the complete mitochondrial DNA genome sequence from three of the human bones to establish that the bones were all from the same individual. Significantly, they identified a family group of genes (mtDNA haplotype) as being a group most commonly found in the Near East, which is better known as the Middle East today – the region where John the Baptist would have originated from. They also established that the bones were probably of a male individual after an analysis of the nuclear DNA from samples.

Dr Schroeder said: ‘Our worry was that the remains might have been contaminated with modern DNA. However, the DNA we found in the samples showed damage patterns that are characteristic of ancient DNA, which gave us confidence in the results. Further, it seems somewhat unlikely that all three samples would yield the same sequence considering that they had probably been handled by different people. Both of these facts suggest that the DNA we sequenced was actually authentic. Of course, this does not prove that these were the remains of John the Baptist but nor does it refute that theory as the sequences we got fit with a Near Eastern origin.’

The Bulgarian archaeologists, who excavated the bones, also found a small tuff box (made of hardened volcanic ash) close to the sarcophagus. The tuff box bears inscriptions in ancient Greek that directly mention John the Baptist and his feast day, and text asking God to ‘help your servant Thomas’. One theory is that the person referred to as Thomas had been given the task of bringing the relics to the island. An analysis of the box has shown that the tuff box has a high waterproof quality and is likely to have originated from Cappadocia, a region of modern-day Turkey. The Bulgarian researchers believe that the bones probably came to Bulgaria via Antioch, an ancient Turkish city, where the right hand of St John was kept until the tenth century.

In a separate study, another Oxford researcher Dr Georges Kazan has used historical documents to show that in the latter part of the fourth century, monks had taken relics of John the Baptist out of Jerusalem and these included portions of skull. These relics were soon summoned to Constantinople by the Roman Emperor who built a church to house them there. Further research by Dr Kazan suggests that the reliquary used to contain them may have resembled the sarcophagus-shaped casket discovered at Sveti Ivan. Archaeological and written records suggest that these reliquaries were first developed and used at Constantinople by the city’s ruling elite at around the time that the relics of John the Baptist are said to have arrived there.

Dr Kazan said ‘My research suggests that during the fifth or early sixth century, the monastery of Sveti Ivan may well have received a significant portion of St John the Baptist’s relics, as well as a prestige reliquary in the shape of a sarcophagus, from a member of Constantinople’s elite. This gift could have been to dedicate or rededicate the church and the monastery to St John, which the patron or patrons may have supported financially.’

The scientific analysis of the relics undertaken by Tom Higham and Christopher Ramsey at Oxford, and their colleagues in Copenhagen was supported by the National Geographic Society. The documentary ‘Head of John the Baptist’, featuring the scientists’ work is due to be shown at 8pm on 17 June 2012.