Interview by Matthew Barrett

In the March issue of Credo Magazine, “Make Disciples of All Nations,” they interviewed Kenneth Stewart, Professor of Theological Studies at Covenant College and the author of Ten Myths About Calvinism (IVP). Here is what he had to say about Calvinism and Missions…

Calvinism is largely anti-missionary. True or False?

It is historically false. Surprisingly, the charge that it is true seems to have grown up especially since 1960 when it was given respectability by the Southern Methodist University, Perkins School of Theology professor W. Richey Hogg. More recently, the charge has been repeated by the late historian of Southwestern Baptist Seminary, William Estep and the evangelical apologetics writer, Norman Geisler. A better knowledge of mission history would have kept them from making this indefensible claim.

What about the Reformers? Did Luther, Calvin, and others care about evangelism and missions?

In the sixteenth century, transoceanic missionary activity required both a supportive monarchy and a national program of overseas expansion. As neither Switzerland nor Saxony were maritime nations, their transoceanic missionary efforts awaited developments beyond their control. Until those developments came, Lutheranism concentrated on the missionary penetration of adjacent territories (Poland, the Baltic countries and Holland). Swiss Reformed missionary penetration of Holland, France and Hungary ran along similar lines. And it was just as perilous work as missions to the tropics.

Many may be unaware that several “Genevan Calvinists” sought to take the gospel to Brazil. Who were these men and what is their story?

In the 1550’s, largely-Catholic France (which was itself playing colonial catch-up with neighboring Spain and Portugal) determined to try an adventure in South American colonization. Though they were unwelcome there (given the prior Spanish and Portuguese division of the continent) they focused their energies on an island off Brazil’s coast. But not enough French Catholics were willing to go on the colonial adventure and so Huguenots were welcomed (Genevans among them). These made a serious attempt to evangelize the aboriginal peoples on the Brazilian coast before being ordered home by the unsympathetic colonial governor.

Were Calvinists among some of the early settlers in the New World and if so what were their methods in sharing the gospel with Native Americans?

There were two notable efforts in Puritan New England. Puritan donors in Cromwellian England raised funds to assist the ministries to Indians of Richard Mayhew on Martha’s Vineyard (an island off Cape Cod) and of John Eliot, who travelled west of his frontier home of Roxbury, MA. The strategy of each was to organize distinctly Christian villages (called ‘praying towns’) for converted Indians and to as rapidly as possible produce Indian versions of the Scriptures with native preachers responsible for the proclamation. This came with amazing speed.

The Synod of Dort is famously (or infamously!) known for its defense of the doctrines of grace against the Arminian Remonstrance of the day. Do we see any signs of missionary zeal among the representatives at Dort?

More than is realized, there was a strongly pietistic element among the Dutch delegates to this international Synod hosted at Dordrecht 1618-1619. This same Dutch Reformed pietism saw in the far-flung efforts of the Dutch East India Company to SE Asian regions such as the present Sri Lanka and Indonesia (formerly Portuguese territories) an opportunity for company chaplains to do missionary work among the native peoples. This happened before Eliot and Mayhew were at work in Massachusetts.

Thanks to Jonathan Edwards, we are left with the diary of David Brainerd. What kind of legacy did Brainerd leave behind in his efforts to preach the gospel to the Indians?

Globally, the missionary devotion and example of Brainerd was transmitted by President Edwards’ Memoir of Brainerd. We know for a fact that it was in turn influential in fixing the outlook of subsequent missionaries to the East such as William Carey and Henry Martyn.

Calvinistic Baptists were among the pioneers of the modern missionary cause. What was the significance of William Carey’s mission to India and the foundation of the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792?

Carey in particular, but also his circle including such persons as Andrew Fuller, were fully cognizant of earlier Reformation-based missionary effort – both in Massachusetts and in South India. Carey and his circle organized a non-ecclesiastical society of the like-minded that would, in due course, act like a ‘leaven’ to influence their (and other) denominations to officially sponsor overseas missions.

How did William Carey handle the protest from hyper-Calvinists that “when God pleases to convert the heathen, he will do it without you”?

There is actually some dispute as to whether these words of spoken objection were actually uttered. But if they were spoken, they were not necessarily the sentiments of an indolent Christian. There was an old attitude, left over from before the days of transoceanic exploration, that—since God is free to do all things—He might also have a way of saving those beyond human reach. But Carey and his circle, full of the new knowledge of the world mediated through the published travel journals of Captain Cook, understood and were made confident of the fact that nations not long before reckoned “beyond reach” were now, in the days of regular transoceanic navigation, made accessible. It was time for the right use of means.

Many Southern Baptists today argue that a zeal for Calvinism has undermined missions. From a historical standpoint, does such a charge hold water?

My personal view is that the reason why these charges were not made longer ago than 1960 is that before that time, fair-minded observers of world missions could plainly observe that missionaries of Calvinist sympathies were more than pulling their weight. The noted missionary scholar Samuel Zwemer pointed out in 1952 (for instance) that Calvinists had been the pioneers of Protestant missions to Arab and Muslim societies. Such charges, when made today, strongly suggest ignorance of the historical record.

Are you encouraged by what you see in our day when it comes to Calvinists taking the gospel to the lost throughout the world? Where might there be areas of improvement?

This is a difficult question. As a Presbyterian, I cannot speak for what is taking place in the SBC. But I am conscious that the missionary energies (as well as other energies) of the church in the West are being sapped by materialism and that, in this existing context, scarce congregational resources are being diverted more and more into short-term missionary ‘stints.’ Moreover, not all evangelical and Reformed seminaries are maintaining their former levels of instruction in missions in this era of budgetary constraints. At very least, this is no time for evangelical Calvinists to be resting on the bare historical record of how our convictions have, in past, promoted missionary sacrifice; we must demonstrate that these same principles are operative now.

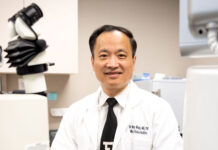

Kenneth Stewart is Professor of Theological Studies at Covenant College. He is the author of Ten Myths About Calvinism (IVP).