By Mark Ellis

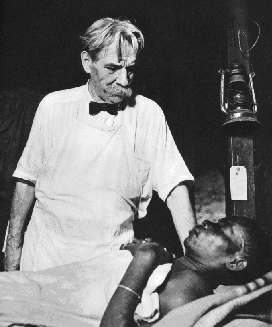

Nobel prize winning physician and theologian Albert Schweitzer worked at the missionary hospital he founded for more than 40 years before he saw his first case of appendicitis among the African natives. Cancer was completely unknown when he first reached the interior lowlands of West Africa in 1913.

“On my arrival in Gabon, I was astonished to encounter no cases of cancer,” Schweitzer noted. “I can not, of course, say positively that there was no cancer at all, but, like other frontier doctors, I can only say that if any cases existed they must have been quite rare.”

It is not as if Schweitzer saw few patients. In the first nine months after he set up his practice, he ministered to 2,000 patients. Over the next four decades, he saw an average of 30 to 40 patients each day and performed three operations a week. By the 1930s, he began to see the first cancer cases emerge, and formed his own conclusions.

“My observations inclined me to attribute this to the fact that the natives were living more and more after the manner of the whites,” he said.

Gary Taubes, a brilliant researcher, chronicles these historical reports from missionaries and other doctors on the frontiers of medicine in his book, “Good Calories, Bad Calories: fats, carbs, and the controversial science of diet and health.” (Anchor Books) Taubes convincingly demonstrates that diseases common to Western civilization emerged in native populations after they adopted a Western diet.

“The absence of cancer in these populations was profound,” Taubes observes. “There’s no reason to think these missionary doctors were not smart enough to know what they were seeing,” he says. “You could get recognized in a British medical journal at that time if you discovered cancer in a black African.”

On the other side of the world from Dr. Schweitzer, Dr. Samuel Hutton began treating patients – primarily Eskimos — at a missionary hospital on the northern coast of Labrador in 1902. Among Eskimos isolated from European settlements, he could not find any cancer, asthma, appendicitis or other “European” diseases. Hutton discovered the Eskimo was a meat eater and the vegetable portion of his diet was practically non-existent.

Even today, in the more isolated Eskimo villages of Alaska, natives still consume about 80-90 percent of their diet from fish, seal, caribou, walrus, eggs, beaver, and other small mammals. Less than five percent of their diet comes from fruit and vegetables, according to naturalist Karen Dodd, a resident of Chugiak, Alaska.

“What both Schweitzer and Hutton had witnessed during their missionary years was a ‘nutrition transition,’ Taubes notes. “The more civilized and more westernized the population, the higher the cancer rates.”

“Through the 1960s breast cancer was virtually nonexistent in the Inuit,” he adds. The Inuit are the indigenous people who inhabit the Arctic region, which includes Alaskan Eskimos. (The Inuit of the Canadian arctic consider Eskimo a pejorative term.)

Taubes also relates the observations of Hugh Trowell, who spent 30 years as a missionary doctor in Kenya and Uganda, beginning in

1929. When Trowell first arrived in Kenya, he noticed the Kenyans were as thin as “ancient Egyptians,” yet when he dined with them they always ate their fill and had leftovers they gave to their domestic animals.

By the 1950s, fat Africans were a more common sight, and in 1956, Trowell diagnosed his first case of coronary heart disease in a native East African, but this was someone who consumed a Western diet for 20 years.

Trowell left East Africa and returned in 1970 to find an amazing spectacle: the towns were full of obese Africans and there was a large diabetic clinic in every city.

After examining 150 years of records and medical research, Taubes believes it is essential to remove sugar, white flour products, and other refined carbohydrates to maintain a healthful diet and avoid diseases such as cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, gout, appendicitis, and a host of other chronic diseases.

“There is a relationship between insulin and cancer,” he notes. “What you want to do is keep insulin levels as low as possible.” Taubes rejects the vegan approach to diet and health; his recommended diet very closely resembles the Atkins diet.

“The one nutrient that doesn’t stimulate insulin secretion is fat,” he says. “The best way to keep insulin low is to switch to a diet that is mostly fat, an animal products diet – that’s the Atkins diet.” The Atkins diet is a low carbohydrate diet created by Dr. Robert Atkins, based on his bestselling book launched in 1972.

A leading researcher at one of the Harvard cancer research centers recently told Taubes he had switched to an Atkins diet as a preventative diet for cancer. Another leading figure at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center who has done research on insulin, blood sugar, and cancer also switched to the low-carb diet “because he doesn’t want to get cancer.”

The researcher told Taubes he had to keep his somewhat controversial dietary choices quiet at Sloan Kettering because it might be perceived as food faddism. “It’s not hard to get people to agree that sugar and refined carbohydrates are harmful,” Taubes says. “But getting people to accept that saturated fat is good for them sounds like quackery.”

Recently, studies have demonstrated that low levels of insulin inhaled in a nasal spray reversed or halted the progress of Alzheimer’s disease in a study group. Some have even suggested that Alzheimer’s may be a form of diabetes in the brain.

“When you have high levels of insulin in the blood, such as when you have diabetes or eat a high carbohydrate diet, you get low levels in the brain,” Taubes notes. He says the link between sugar and Alzheimer’s is probably there, but the mechanism is not completely understood.

Still, mining the historical records of missionary doctors and others on the frontiers of medicine more than a century ago may help untangle the mysteries of our deepest health concerns today.

AMEN! I’m a type 1 diabetic and have been so helped by the low-carb/atkins/paleo diet! No way can you eat carbs and have any measure of blood sugar control. All my life it was preached to me that high blood sugar was bad and that insulin is the answer. Well, yes, that’s true, but high INSULIN is also bad, very bad, for you.

We’ve got to get the word out on this. The American diet is killing us.

I always feel better following a diet closer to the Atkins Diet. Exercise isn’t mentioned in this article, but it stands to reason that it plays a huge part in these differences also. The bigger we are – we slow down on excise too. I had gastric bypass surgery some years ago, so I have to concentrate on my protein first – all the rest I can take suppliments for. This puts me back to meat, cheese, and eggs, legumes. If there’s any room left, veges and fruit, whole grains. Sound familiar? Atkins.

the article mentions refined sugars, but does that include potatoes and rice?

I believe the author would tell you to minimize potatoes and white rice. Stick with the whole grains in moderation.

This rings true to a book my wife is reading called “The China Study.” Whites’ influence on cultures leads to what that author calls “diseases of affluence,” as opposed to third world countries’ “diseases of poverty.”

Good stuff , Many thanks. It’s fab to find a useful bloglike yours, especially with goodposts like the one above. Many thanks and keep up the fab work.

As a missionary in Papua New Guinea for 24 years, I have often wondered about cancer rates. I am not a doctor but lived in the deep interior. Several things come to mind: people die very young. If the life expectancy is 50 for women, it is not a shock that there is less observable cancer. At the same time, when we’ve managed to get people flown out for diagnosis, they did have cancer but is is usually discovered very late. There are many “unexplained” deaths among tribal people who are eating the ultimately healthy diet. There are just a host of other things killing them.

Many of my missionary friends have had cancer and a good number died. We ate like the people around us, except we had more protein. Late diagnosis was a big issue. I observed, that those who had chronic dysentry were more inclined to discoverd colon cancer. That is a laymen’s view certainly one that is born of living amoung remote people for an extended period.

Comments are closed.