By G. Wright Doyle —

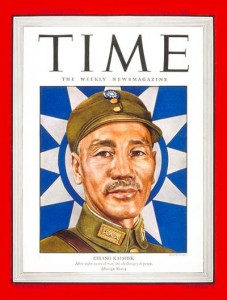

He was a polarizing figure who inspired respectful admiration or disgust and derision. He led the Republic of China during World War II, but after a bloody civil war with the communists his government was forced to retreat to Taiwan in 1949. The story of his spiritual journey reflects his turbulent life, which was often filled with contradictions.

Chiang Kai-shek was born to Chiang Shu-an, a salt merchant. His mother, Wang Tsai-yu, was a devout Buddhist who sought to inculcate the tenets and practices of her faith in her son from infancy.

As a child, he was known for his tendency to assume command of others, expecting obedience. The death of his father when he was very young forced his mother to work hard to support her son. As he watched her dealing with unscrupulous people, an intense rage started to burn in him, and he began to see himself as part of an exploited people.

He reacted to these perceived injustices by turning in upon his own resources, spending a great deal of time alone, surrounded by mountains and streams and meditating upon his own future course.

At the age of fifteen, he married nineteen-year old Mao Fu-mei, who was functionally illiterate. The couple seems to have been close for the first two months of their marriage, but Chiang’s mother rebuked him for uxoriousness. In response, Fumei dutifully distanced herself and the two drifted apart.

As a young man, Chiang was known as a promiscuous womanizer, despite being married and having a son. His first marriage fell apart as his wife, who did not share Chiang’s passion for politics and revolution, complained of his frequent absences. He often beat her, and at least once dragged her by her hair down a flight of stairs. Finally, the two settled upon a relatively amicable divorce, though his wife grieved deeply. Chiang Ching-kuo was their only son.

After their divorce, Chiang was reported to have several concubines, one of whom, Zhang Ah Feng, “Jennie,” he reportedly married in 1921. At that time he contracted a form of venereal disease.

After graduation from a military academy in Japan, where he met Sun Yat-sen, Chiang become an enthusiastic supporter of the Chinese nationalist revolution, and joined the Tongmenghui (Sun’s organization).

Return to China

Chiang returned to China to participate in the Xinhai Revolution, which overthew the Qing Dynasty. He eventually became a trusted associate of Sun, who appointed him founding commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy in 1918, when Chiang also joined the Nationalist Party (KMT). He succeeded Sun in 1925 as leader of the KMT upon Sun’s early death.

In 1926-1927 he unified much of the country, defeating warlords and breaking with the Communist Party, whose members he purged from the KMT.

In his personal life, Chiang fell in love with Soong Meiling, the daughter of wealthy businessman and former missionary Charlie Soong. There seems to have been a political deal worked out through the mediation of Meiling’s sister Ailing, wedding the Soong family wealth and connections to Chiang’s military and political assets.

When Chiang sought to marry Meiling, the strong Christian identity of the Soongs meant that their daughter could not be joined to a non-believer. Meiling’s mother asked Chiang whether he would become a Christian. He replied that he would not change his religion to marry Meiling, but he would read the Bible and pray for God to show him what he should do.

Permission was granted, but Methodist church law forbade a church wedding between a Christian and an unbaptized person. It was also doubted whether Chiang had been properly divorced from his first wife, and there were persistent rumors about Jennie, whom Chiang had sent off to America without divorcing. Chiang produced proof of his divorce and discounted the stories about Jennie. Bishop Z.T. Kuang went to the Songs’ house to pray for the couple and pronounce a blessing upon them after a lavish civil ceremony on December 1, 1927.

![Kai-Shek Chiang [& Wife]](https://www.godreports.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Chaing-Kai-shek-with-wife-300x243.jpg)

Chiang formed a Nationalist government inNanjingin 1928, with himself as virtual military dictator, though many democratic and modernizing reforms were undertaken during the so-called Nanjing Decade (1927-1937).

A pledge to God

In the midst of a military campaign against a rebellious general, Chiang found himself surrounded, with capture and death imminent. He spotted a local Christian chapel, entered it, and told God that he would become a follower of Christ if he survived. A heavy snowstorm impeded his enemy’s advance, and Chiang’s forces gained the victory. He was baptized by Bishop Kuang in 1930. When asked why he had become a Christian, he replied, “I feel the need of a God such as Jesus Christ.”

In addition to his wife’s impact, he may have been influenced by the Christians in his government, since seven out of ten high officials in Nanjing were believers. Quickly, Meiling became an essential source of strength and support. She helped Chiang keep up with world news, reading and digesting English publications daily; introduced him to Western literature, music, and culture; served as personal advisor, ambassador, and interpreter.

Their marriage, though outwardly harmonious, was sometimes marked by conflict and tension, aggravated by Meiling’s extravagance, domineering personality, and possible infidelity, as well as by his intense emotions, bad temper and inability — or unwillingness — to engage in marital sexual relations.

Close friends and associates have borne abundant testimony to Chiang’s daily Bible reading, prayer, and open affirmation of his faith in Christ. Some contemporaries say they noticed that after his baptism he seemed to believe less in force and more in conciliation.

During one notable incident, after he gained release from captors in Xi’an, he stated that he had been strengthened during his ordeal by reading the Bible and entrusting himself to God’s care, so that he did not fear death and thus would not give in to their threats and demands.

“The greatness and love of Christ burst upon me with new inspiration,” Chiang said, “increasing my strength to struggle against evil, to overcome temptation and to uphold righteousness…” He further claimed that he forgave the two main perpetrators because of the example of Christ on the Cross.

Family devotions

A visitor to his house in Chongqing was stunned by a significant time of family prayer after dinner, during which the General asked God for strength and energy for his soldiers and himself, requested that God would help the Chinese people not to hate the Japanese; and calmly placed himself and his nation in God’s hands, imploring divine wisdom to know how to serve God the next day.

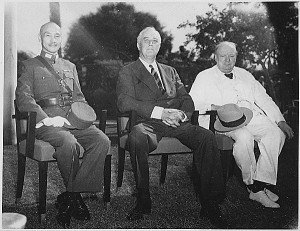

He continued to seek to eliminate the communists, despite Japan’s increasing encroachments and domestic calls for stiff resistance to the Japanese. Finally, after the Xi’an Incident in 1936, he was forced to enter into an uneasy alliance with the communists in order to fight the Japanese. He led the Republic of China during the Second World War, and was elected President of the Republic of China in 1948, but was forced to retreat with many members of his government and army to Taiwan in 1949.

Chiang’s Christian commitment found expression in his diaries, his public statements, regular church attendance, and the open support of both Chinese and foreign Christians. One of the most public manifestations of his ethical convictions in his early years was the New Life Movement, an attempt to reform Chinese civilization and morals on the basis of Confucian principles, with some admixture of Christianity. Chiang and his wife poured enormous energy, time, and resources into this campaign, for which he solicited the help and support of Christian missionaries. They generally approved of the project, and in some places it took on a Christian flavor. The invasion of China by Japan put a virtual end to this ambitious undertaking, as it did so much else that the Nationalist government was attempting.

In later years, Chiang was heavily involved in the translation and publication of “Streams in the Desert” into Chinese, and worked closely with John C.H. Wu’s translation of the New Testament, going over the draft and making suggested corrections many times. The front piece of Wu’s version of the Psalms indicates that it was produced “under the editorial supervision of Chairman Chiang.”

Wu found enough material about Chiang and his faith to write a 265-page book on his spiritual life, published in 1975. His diaries reveal his constant reliance upon God for wisdom and strength. Western missionaries who knew him in Taiwan report that he seemed humble, gentle, and genuine in his faith when they saw him in church each Sunday, and had no reason to doubt the sincerity of his Christian profession.

This assessment was shared by his personal chaplain. Though the general populace of Taiwan were surprised to see a large cross at the head of the funeral cortege, and to read at the opening of his will that he had been “a follower of the Three Principles of the People and of Jesus Christ from his youth,“ those who had known Chiang were struck by his personal inconsistencies.

Personal contradictions

On the other hand, some of his ideas, actions and personal characteristics seem to belie the depth of his faith, or at least its impact upon his conduct. Chiang read widely in the Confucian classics and in Chinese history, and believed strongly in the value of China’s cultural heritage, especially Confucianism. His Christian sermons seemed unclear on the distinctions between personal salvation and national recovery.

His long and consistent alliance with the Shanghai underworld made him complicit, at least to some degree, in their corruption and cruelty; likewise, his reliance upon his own secret police, which engaged in countless acts of brutality.

Reports of corruption on a grand scale by his wife’s family call his own integrity into question, though he had no power to control them; still his nepotism is undeniable. His decision to breach the levees of theYellow River in order to stall the advance of the Japanese, and then again to halt the Communists, led to the deaths of thousands and deprived many more of their homes and livelihood. Though his role in the military suppression of Taiwanese dissent in the infamous February 28 incident is unclear, his active oversight of the ensuing White Terror is well established.

Chiang’s positive character traits included extraordinary personal courage, a huge capacity for work, a very strong will, and immense stamina.

On the other hand, he was notorious for refusing to take advice, or even to seek the counsel of advisers. He brooked no disagreement, and would fly into a rage when criticized. A mediocre military leader, he issued orders from afar without any real knowledge of battlefield conditions, and then altered his plan without notice.

More than once, he ordered loyal troops to fight to the death, knowing that their resistance was fruitless. Some of his closest companions considered him to be an arrogant egotist. There is evidence that he often said one thing and did another, or said one thing to one person and something else to another. Though he projected an image of imperturbable calm in public, he could cry like a baby behind closed doors.

His lifelong commitment to Confucianism makes some wonder whether his fundamental faith was more a matter of traditional Chinese ethics than Christian belief. Did his extraordinary self-control in public stem from dependence upon God, or upon the inner strength he had long learned to cultivate?

In defense, many have argued that Chiang’s autocratic leadership style is simply the norm for Chinese, and can be found in some of the most outstanding Chinese church leaders even today. Also, he was surrounded by mortal enemies and spies, and could really trust no one. His murderous purge of communists in Shanghai was undertaken only after his enemies had formed a rival government, committed atrocities and put a price on his head. Further, war compels one to make decisions that will cost many lives in order to save more people. It is believed that he matured in Christian character as he grew older and that a Christian’s true heart can be known only to God.

If his private diaries, public pronouncements, consistent support of Christian churches and foreign missionaries, and active involvement in the production of Christian literature which we have noted above mean anything, then we may perhaps say that Chiang Kai-shek’s Christian career represents the halting, stumbling, but steady pilgrimage towards the Celestial City of a sinner saved by grace. — edited by Mark Ellis

If you want to know God personally, go here

G. Wright Doyle is Director, Global China Center; General Editor, Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA.

I like how you addressed the shady and negative aspects of Chiang’s life and characteristics. I’m not sure how I feel about Chiang, but as of right now, I am totally captivated by Dr. Sun.

I’m trying to find stuff on Dr. Sun and his faith, but there is so little of his own personal accounts.

Second to that, I’m interested in Charlie Soong and the Soong sisters as well.

蔣總統萬歲!

Long Live President Chiang!

總統 蔣公, 您是人類的救星, 您是世界的偉人

總統 蔣公, 您是自由的燈塔, 您是民主的長城

內除軍閥, 外抗強鄰, 爲正義而反共, 圖民族之復興

蔣公, 蔣公, 您不朽的精神, 永遠領導我們

反共必勝, 建國必成, 反共必勝, 建國必成!

President General Chiang, you are the savior of mankind, you are the greatest person in the whole world.

President General Chiang, you are the lighthouse of freedom, you are the Great Wall of democracy.

|: Eliminated the warlords, fought foreign aggression, opposed communism for righteousness, to seek the renaissance of our race!

General Chiang, General Chiang, your everlasting spirit will forever guide us.

We shall win against communism, we shall build the nation, we shall win against communism, we shall build the nation!

Excellent information. I read the book ‘The Secret File on John Birch’ (good book showing that missionary activity went on during the war and also that the US subtly undermined the Nationalists) and it was mentioned that a pamphlet entitled ‘Why I Am a Christian’ by Chiang Kai-Shek was a great tool for sharing and gaining acceptance of Jesus and the Gospel. I was surprised to see his faith barely mentioned, especially when it seems to be a significant part of his life, whereas his Confucian influence is expounded upon greatly. I am reading ‘Mao: The Unknown Story’ and Mao comes across as a selfish, narcissistic, intelligent, and rebellious character. I quote at length from a book Mao wrote at age 24:

“I do not agree with the view that to be moral, the motive of one’s action has to be benefitting others. Morality does not have to be defined in relation to others…People like me want to…satisfy our hearts to the full, and in doing so we automatically have the most valuable moral codes. Of course there are people and objects in the world, but they are all there only for me.”

I believe that there are a great many mysteries that God will show us when we get to heaven, but one that I believe God will show is how America deceitfully turned its back on Chiang Kai-Shek who could have retaken China from Taiwan if we had just supported him a little. In fact any support from us at all would have helped him hold China, instead we call him Chiang ‘cash-my-check’ at let Mao kill 70million Chinese and let what would have become the greatest christian nation in the history of the world be lost to communism. The repercussions of this are still felt all over Asia, because China is the intellectual heart of East Asia and China was on the verge of converting, with hundreds of thousands of Chinese accepting Jesus at the turn of the 20th century into WWII. That this history is forgotten and Mao is still considered a friend of the people till now is a joke, at no time does he express sympathy for their plight in his early writings. May God have mercy on us, even so, come soon Jesus.

cool

Comments are closed.