By Mark Ellis –

They called it the “Miracle on the Hudson” when Captain Sully Sullenberger landed his US Airways flight on a placidly flowing Hudson River in 2009 and all 155 people aboard were rescued by nearby boats.

But an even more dramatic and miraculous rescue took place in the frigid waters off Nome, Alaska, as seven missionaries were plucked from the Bering Sea following a plane crash in 1993.

The seven had just completed an impactful mission in Russia’s Far East, bringing three thousand pounds of food, a thousand pounds of medicine and 500 Bibles to the town of Laverntija, which had no existing church.

“I baptized the former head of the communist party,” recalls Dave Anderson. “She gave her life to the Lord and the next day we flew back.”

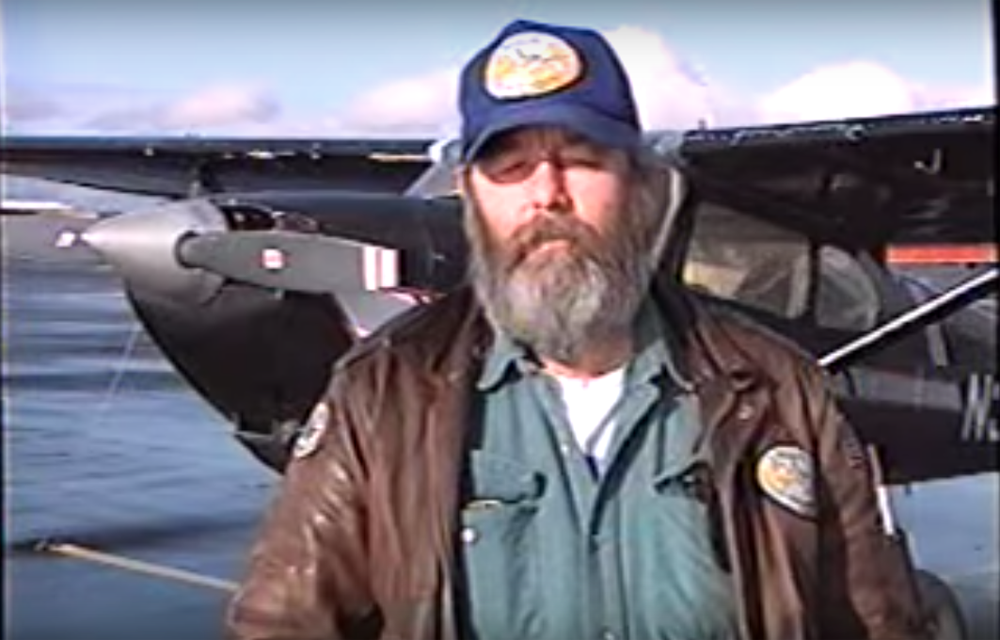

Dave and his wife Barb founded Fellowship Ministries in 1975 and later, the Shepherd’s Canyon Retreat center, where they minister to Christian leaders in need of renewal and refreshing. He recounted his story to God Reports; other details for this story were found in a documentary about the rescue made by Terry Burge.

On the team’s return flight to Nome, Barb happened to glance at the instrument panel and noticed the gas tanks were not full.

When Chief Pilot Dave Cochran refueled the plane, he thought he had enough for at least two hours of flying time. They needed one hour and 30 minutes to make it to Nome.

After they left Russia, they refueled with American fuel because the Russian aviation fuel is so poor it damages engines. As a result, they were ferrying empty gas cans back to the U.S. to have them refilled and sent back. Those empty gas cans turned out to be one of the important details in God’s plan to save their lives.

Before their plane departed from Russia, a guard came up to their group and said, “Good luck.” They would need more than luck in the next few hours.

The plane’s initial climb was turbulent. “I was praying, Lord, could you just clear the skies for us and give us a smooth flight? Barb recalls. “We rose and rose and rose what for me seemed an eternity. It seemed like we were going higher and higher and all of a sudden we broke into the most clear, sunny blue skies. It was beautiful and the sun was so bright and I said, Thank you Jesus. I’m grateful for this.”

But Barb kept looking at the gas gauges and they were getting perilously low. She turned to another woman on their team and said, “Look at the gas gauges.”

Dave had fallen asleep and was blissfully ignorant of the impending danger.

Pam Swedburg woke up to the sound of a chug-chug. The first of two tanks for their twin-engine plane had run out of fuel.

“All of a sudden there was a side to side motion, unlike anything I had ever felt before in a plane,” Barb recalls. “It’s an eerie feeling and it frightened me.”

Dave woke up abruptly and looked around. Everyone’s eyes were suddenly very wide as the reality of the situation began to hit them.

The pilot realized he had about five minutes left on the remaining engine. He radioed air traffic control and declared an emergency. “After the second engine quit, I tried to keep it at 130 miles per hour glide speed,” Pilot Cochran says. “I could see we weren’t going to make it to land.”

The team members began to pray in earnest. “It took a minute to fall about 3500 feet, during which time we were having an informal prayer meeting,” Dave says.

Plane crash

Barb heard their pilot shout “May Day! May Day!” into the radio and then “Brace for impact!” The plane hit the water at 90 miles per hour.

The water slammed into the windshield and flew up the sides of the plane ferociously. Everyone was still conscious and miraculously, there were no casualties from the impact. The plane was mostly intact, but water was gushing in and it would sink within minutes.

Surprisingly, no life vests were on board. “Everybody out! Hang on to one of those gas cans,” Captain Cochran yelled out. “That’s our flotation gear.”

“Out the plane we went and a minute later the plane sank and we found ourselves in three to five foot swells,” Dave recounts. He tried to stay close to Barb, but the swells began to separate them.

The water temperature was 41 degrees Fahrenheit. At that temperature, someone struggling in the water can become disoriented within five minutes and lose consciousness in 30 minutes. Could rescuers arrive in time to save them?

Pam Swedburg floated close to Don Wharton. He grabbed her legs underwater with his legs and would not let go, which probably saved her life.

Brian Brasher, 23, a teacher and sound engineer, was the youngest member of the mission team. He began to yell out Scripture: ““God is our refuge and our strength, a very present help in trouble.”

A few minutes later he hollered, “This is the day the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it.” His voice carried across the water as if he had a microphone, but Dave thought he had chosen the wrong verse for that moment.

Many in the group were praying aloud and shouting encouragement to hang on to their gas cans and keep afloat, but it was difficult as three to five foot swells crashed over their heads.

The impact site was 22 miles from Nome and two miles from an uninhabited island called Sledge Island. While someone mentioned trying to swim to the island, they quickly realized that would be impossible in the freezing water and it would be best to stay together.

“Once the shock wore off we were so numb we couldn’t feel how cold the water was,” Dave recounts. Barb recalls her teeth beginning to chatter uncontrollably.

God’s rescue plan

In God’s providence, there happened to be a plane flying over them at the precise moment of the crash. The plane overhead was one hour behind their scheduled flight time. Terry Day, the pilot of that Bering Air flight, looked out the window and noticed a small splash.

“I thought it was a whale,” Day says. “I contacted the (air traffic control) center and they said there was an aircraft having some difficulty. They said they were trying to make it to Sledge Island. Immediately I knew the splash I had seen had something to do with that airplane.”

If Day’s plane had not been one hour late, he would not have seen them crash into the sea and rescuers would not have located the missionaries in time to save them.

Day turned his plane around and began to fly in a search pattern. Suddenly a passenger next to him shouted, “I see somebody in the water!”

He radioed air traffic control and reported, “There’s people in the water down here and some wreckage.”

Traffic controllers contacted Nome Flight Service, closest to the crash. They located an Evergreen helicopter parked at their hangar, but initially had difficulty finding its pilot. “I was just about to go fishing when I got the call about the aircraft in distress,” says Pilot Eric Penttilla, with Evergreen.

Half the time, the Evergreen helicopter would be in service, making deliveries, and not available for this sort of emergency.

Penttilla agreed to be part of a rescue team and grabbed two members of Nome’s volunteer fire department. One of firefighters picked up seven body bags from the station, knowing no one had ever survived a plane crash in the Bering Sea.

It was understood that if a plane went down there, life expectancy without survival suits would be very brief.

One obvious problem was their team was not equipped for an ocean rescue. “We didn’t have any gear for that type of rescue,” says Randy Oles, captain of the Nome Fire Department. “Luckily there was a piece of rope in the helicopter.”

As the missionaries floated in the icy water, they struggled to maintain their grip on the gas cans. When hypothermia sets in, one begins to lose strength and control of the arms and legs.

“Because of immobility and inability to use the arms and hands, before you die of hypothermia you will probably drown,” hypothermia expert William Mills noted in the documentary about the rescue.

When the body’s core temperature drops to 88-86, people go into a coma, what Mills calls

a “metabolic icebox.”

Forty minutes after the crash, the Evergreen helicopter made it to the site. They hovered overhead and tried to get as close to the water – and the survivors — as possible, but the pilot had to time the swells to avoid a second disaster.

“The helicopter was hovering over the water and at some points the belly was going into the water, something you don’t do,” Dave recalls.

Pilot Penttilla had to watch out the left side of his chopper for waves. “A crest came and I had to raise the helicopter up and as the trough came I had to go back down,” he says.

They were going to rescue Brian Brasher first, but he waved the helicopter toward Cary Dietsch because he knew he was in worse shape. Instead of being rescued first, Brian was rescued last – the ultimate example of sacrificial love.

Cary was losing the strength to maintain his grip on the wire handles of two gas cans. After he was rescued, he said he could have held on for another five seconds, then would have sunk like a stone into the depths.

The pilot of the crashed plane, Dave Cochran, was one of the next to be rescued. “They dropped me a rope with a loop in it, but I couldn’t get my fingers to respond to pull it apart so I could get into it. Then a big wave came and I went underwater,” Cochran reports.

“After I got up to the surface I saw a hand reach down and grab the back of my jacket and from then on it was blank. Being unconscious, my body was shutting down.”

Firefighter Randy Oles ripped the hood off Cochran’s parka and finally got a rope underneath his arms. When Cochran was pulled out he was “deathly white” and appeared to be dead.

Dave Anderson’s body was also shutting down in the water. “I had no strength in my arms and he couldn’t pull me up into the helicopter by himself,” Dave says. But a swell caused the skid of the chopper to plunge beneath the water and Dave’s right leg managed to get on top of it. Finally the firefighter had some leverage to pull Dave up and inside.

The first three pulled out of the water were transported to Sledge Island and deposited on top of its windswept plateau, punctuated by tundra. If they had not crashed near the island, half the team would have perished, according to Dave.

Saving the last two

Meanwhile, a second helicopter arrived on the scene with a young Canadian geophysical surveyor, Dave Miles, aboard. He immediately spotted Barb in the water and knew she was in trouble.

They passed low enough for Miles to attempt to grab her hand, but he missed on several attempts. “It was very difficult because the waves were going up and down,” he recounts.

Then the skid came down and he grabbed her with one hand and got his knees around her neck and feet around her upper body. He shouted to his pilot, “I’ve got a pretty good grip on her.”

Barb had doubts. “I thought this wasn’t going to work. I kicked and squirmed but I couldn’t talk because my head was squished between his knees.”

“How far away is that island?” Miles asked his pilot.

“It’s about a mile,” he said. (It was actually twice that distance.)

“Ok, let’s go to the island.” Miles couldn’t physically pull Barb into the cabin, so they flew with Barb dangling perilously by her neck for two miles until they got close to the island.

But then she began to slip from his grip. “Go down, she’s slipping!” Miles shouted to the pilot.

Shockingly, she slipped out of his hand and legs and fell into the water a second time from a height of 20 feet, narrowly missing two boulders and crashing waves, about 30-40 feet offshore.

There was no beach, only a rocky coastline and waves pounding around her.

“We couldn’t get the helicopter anywhere close to get her because the waves were too high, so I told Walt to take me into shore and I would go out and get her,” Miles recounts. As soon as Miles went into the water he felt like the wind was knocked out of him. “I didn’t imagine it could be so cold,” he says.

“I was dying in the water,” Barb recalls. “The Lord gave me this peace and I heard this voice behind me and I came to consciousness and I turned toward the voice and there was Dave Miles and he said, ‘You can make it. Come to me. I can’t come to you.’

She had drifted enough that her feet could touch the rocky bottom and she could walk toward Miles, who pulled her in to the shore.

Brian was the last person to be rescued, after 70 minutes in the water. “I felt like I was in a tug of war with Satan,” he recounts. “We had been to Russia doing God’s work and honoring him, but Satan was trying to get us back. I felt like he was under the waves, tugging at my legs, trying to pull me under the water.

“I said, ‘Satan, you can’t do this to me because I’m not yours. I’ve been bought with the blood of Jesus Christ.’

Finally, all seven were pulled from the icy waters and deposited on top of Sledge Island, but they were not in very good shape. When Dave first saw Barb was alive, he stumbled when he tried to walk toward her. One in the group was slurring his words, another lapsing in and out of consciousness, one throwing up.

I was lying there crying, thanking the Lord for saving us,” says Pam Swedburg. “I knew there was no way I should be here. The power of prayer really does work.”

The team arrived in Nome, with Pilot Cochran and Dave carried off the helicopter on stretchers. “They began to cut off my clothes so they could warm me up with blankets,” Barb recounts. Doctors and nurses began to work on them as they slowly began to revive.

“If any link in that chain had been missing, they would not have survived,” says Pilot Terry Day.

“The fact that their crash was even noticed was miraculous. Absolutely everything involved in that rescue was miraculous. Those of us who believe…our faith was reaffirmed that day.”

Dave Anderson can’t forget their rescuers brought seven body bags with them. “They carried out the most dramatic rescue in aviation history,” he believes. “God can handle what you and I cannot handle.”

He drew me out of the deep waters. He rescued me from my powerful enemy, from my foes, who were too strong for me. They comforted me in the day of my disaster, but the Lord was my support. He brought me into a spacious place; he rescued me because he delighted in me. (Psalm 18: 16-19)

To learn more about Dave & Barb Anderson’s ministry, go here