The Lord told William “Blinky” Rodriguez to forgive his son’s killers, but when he came to the courthouse, he was faced with 30 hostile friends and family of the convicted gang bangers.

“I was beat up in regards to the way my son got killed,” Blinky says. “Then we get to the courthouse and 30 guys are there supporting them. They were looking at my wife and I like WE did something wrong, like we were a piece of garbage. This hatred was trying consume me. It was choking me. I tried to not feed it. I tried to not do war. The weapons of our warfare are not carnal. We came into an agreement to forgive.”

Facing the hate-filled supporters on Jan. 30, 1992, Blinky stood and addressed the Pacoima gang member who shot and killed his 16-year-old son. At the time the teenager was learning to drive stick shift and mistaken for a rival: “David, we forgive you, man. You may have taken Sonny’s life, but you didn’t take his soul. You deal with God now.”

It was an extraordinary demonstration of God’s love, redemption and mercy.

It was an extraordinary demonstration of God’s love, redemption and mercy.

That moment in court also sparked a ministry to save gang-bangers and bring law and order to the streets of Los Angeles. Violence snuffed out his son’s life, and Blinky would dedicate the next decades of his life to snuff out gang violence in LA.

Today, social scientists can’t account for the dramatic drop off of drive-bys and retaliations in LA, with some pointing to California’s three-strikes law and others to social programs.

In the strife-ridden 1990s, there were 1,200 killings a year in LA; now there are a mere 300, Blinky notes.

He gives credit to God and to the 37 staff members serving in the organization he formed, Communities in Schools (CIS), a social service agency focusing on gang prevention and hard-core intervention. (Note: CIS is changing its name to Champions in Service because of restructuring at the national level.”

“I am waiting for the second wave or revival,” Blinky says. “There’s a lot coming. There’s going to be revival in this valley. God allowed a light to be set on a hill that would not be hid. It’s all for the promotion of the kingdom. The church was meant to be in the center. We have to steward our influence.”

Blinky Rodriguez accepted Jesus at a Spanish service in the City of San Fernando, even though he didn’t speak Spanish. He got hooked on martial arts at age 11 in a dojo in nearby Granada Hills. By age 14, he was married and working for his uncle plastering pools for $110 a day. He never graduated high school.

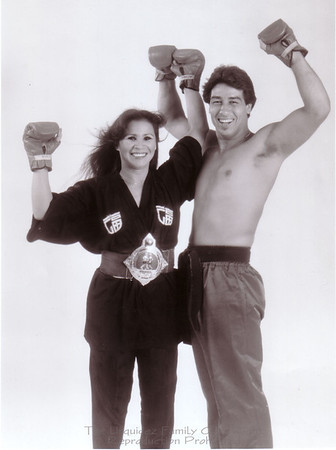

He competed in and won Chuck Norris’ nationwide full contact-to-knockout tournament, which led to the formation of a national team kickboxing in Japan. Along with his brother-in-law, Benny “The Jet” Urquidez, he founded and worked the Jet Center Gym in North Hollywood offering training in martial arts.

He was managing pros and choreographing stunts for movies and attending Victory Outreach Church when his eldest son Sonny, 16, was approached by Pacoima gang members and asked the dreaded question: “Where you from?”

He had been dabbling in gang dress but wasn’t affiliated. “Nowhere,” Sonny replied, as he sat behind the wheel of the car.

David Carmona, 19, fired point blank into the vehicle, killing the youngster. For his brazen and senseless murder, Carmona was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

To the dismay of the district attorney, Blinky forgave his son’s killer in court and asked for leniency for the guy whose car Carmona and an associate used to perpetrate their violence. He was a victim of circumstance, under the influence of tequila when he loaned his car, Blinky says.

God told Blinky the night before the sentencing: “Tell em to their faces you forgive them.”

Blinky’s wife ministered to the killer’s mother when she saw her break down in the courthouse bathroom.

Blinky didn’t let it die there. He began to reach out to gang members of all affiliations. One night, he visited the site where his son was murdered, and finding young hoodlums there, he witnessed to them about the power of God to transform lives.

Two years went by, and he made connections in the community that brought him into the headlines once again. He organized a meet-up in the park of gang rivals to declare a truce in the gang warfare that was scourging LA everyday.

“There was a vicious spirit of murder over our city,” he says.

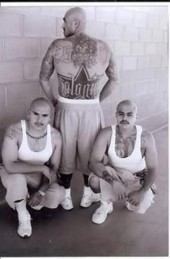

In 1993 on Halloween night in a city park, “shot-callers” from 76 gangs met, listened to Blinky’s testimony and the testimony of gang pioneer Donald “Big D” Garcia, and agreed to end the interminable cycle of gang revenge.

It was a stunning achievement in LA, and it lasted two-and-a-half years.

Blinky held weekly meetings in the park, shared the gospel with gang bangers, and staged football tournaments in which rivals threw pigskin instead of gang signs. He trained gang members in his gym.

Ultimately, it only needed one embittered gang member to blow up the whole unheard-of peace treaty with one incident of violence. While the peace treaty didn’t last, the major thrust to end gang warfare largely remained.

Almost 30 years later, Blinky is still in the hood.

His office staffs 37 social workers who provide tattoo-removal, counseling and job training for “at risk” youth. CIS in the “North Hills” neighborhood of the San Fernando Valley is in the heart of gangland, Blinky observes.

Once, they literally chased police helicopters to get to the crime scene and minister to crying mothers and cool down flaring tempers feeding a spirit of revenge. Now they receive notifications directly from the police, he says.

“This is enemy camp ministry,” Blinky says. “We’re set up right up in the middle of it. We’re not holding a line. We’re behind enemy lines. We’re in his camp.”

His office organized a soccer tournament for Mara Salvatrucha gang members last summer at USC.

Along with his numerous martial arts trophies, Blinky has received abundant recognitions and awards from the City of Los Angeles. When he fought in the arena, he would sometimes grab the announcer’s microphone to proclaim the love of Jesus. Now in front of politicians, the unabashed Christian proclaimed God’s love to city fathers.

CIS in Los Angeles has advocated in City Hall, in the courts, with district attorneys and with social workers. They intercede on behalf of the neglected, crime-weary neighborhoods where boys grow up too frequently without dads and without a viable path to success.

Punitive measures alone won’t solve the problem, Blinky says. There needs to be affirmative programs to mentor and train hopeless youth.

“There’s gotta be balance, not just punitive or probation,” he says. “There’s gotta be some humanity to it. We can’t arrest our way out of this.”

From a young age, boys are “pipe-lined” into the prison system from their first police interactions. Gang injunctions that ban two friends from walking together or playing basketball complicate matters, Blinky says. Then in court, the district attorneys have the most resources and the judges often have deep connections to the DA’s office, creating a system that snares troubled young people.

His own son, David, was wrongly convicted, Blinky says, and served 33 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit because of inequities in the system. David was released three months ago.

Blinky’s first wife died at age 59. After becoming a widower a second time, he remarried his present wife, Gloria. The Jet Center was closed by the 1994 Northridge earthquake. From that moment, Blinky dedicated 100% of his time to his non profit.

CIS has provided $1 million worth of burial plots to needy families to help them avoid falling prey to funeral homes’ exploitative sales strategies, he says.

“This thing continues to mushroom because I’ve been in the desert for a long time,” Blinky says.

Michael Ashcraft sells 10″ bamboo steamers on Amazon to support his journalistic ministry.

Michael Ashcraft sells 10″ bamboo steamers on Amazon to support his journalistic ministry.