By Anthony Gutierrez —

Finally, the FBI caught up with Jack Barsky – and so did God.

For 19 years, Barsky spied on America for the Soviet Union during the Cold War. After the breakup of the Soviet empire, he spied for Russia.

His job was to infiltrate U.S. society and get close to security officials and pry information from them. And the “sleeper agent” went undetected until May 1997 when the FBI finally caught him.

“I came to terms with (the fact that) I did a lot of bad things – never mind breaking laws,” Barsky told Glenn Beck. “I hurt people. I did bad things. I served a bad cause.”

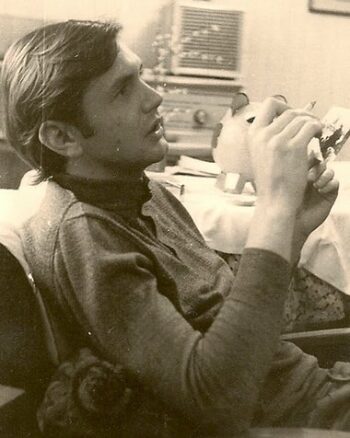

Barsky was born Albrecht Dittrich in East Germany in 1949. In college studying chemistry, he proved he had a brilliant mind and a matching hauteur. When the KGB approached him to work as a spy in America, it conjured up his inner ubermensche – Nietzche’s superman. “I could see the world and I didn’t have to go by the usual rules — I would be above the law,” he told Der Spiegel.

Barsky was born Albrecht Dittrich in East Germany in 1949. In college studying chemistry, he proved he had a brilliant mind and a matching hauteur. When the KGB approached him to work as a spy in America, it conjured up his inner ubermensche – Nietzche’s superman. “I could see the world and I didn’t have to go by the usual rules — I would be above the law,” he told Der Spiegel.

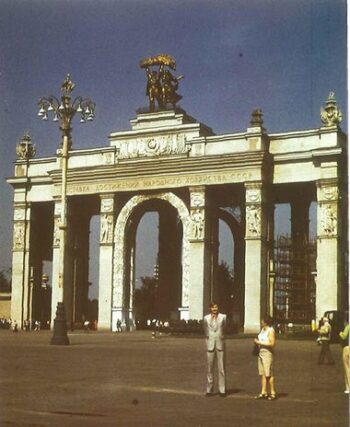

In East Germany, Dittrich learned secret handwriting, Morse code and how to lose a tail. In Moscow, he devoured English, mastering hundreds of words daily.

He was shipped off to America in 1978 with $6,000 in his bags and instructions to assume the position of a businessman and get cozy with politicians and other influential people in Washington. Specifically, he was told to make contact with then-National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

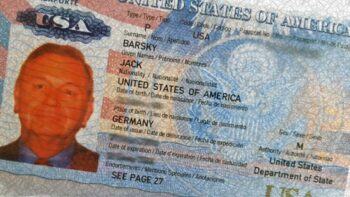

An employee at the Soviet Embassy scored him the birth certificate that would give him the basis to get a passport. He had spotted a tombstone of 10-year-old Jack Barsky who had died in 1955 and procured the birth document.

Under his new name, Barsky first worked as a bicycle messenger in New York, a job that provided him with plenty of opportunity to get to know the city, observe people and learn the intricacies of the city’s commerce.

“The messenger job was actually really good for me to become Americanized because I was interacting with people who didn’t care much where I came from, what my history was, where I was going,” he told the BBC. “I was able to observe and listen and become more familiar with American customs. So for the first two, three years I had very few questions that I had to answer.”

Later, he studied computer science and worked as a programmer for Met Life insurance. If anyone ever asked about his slight accent, he responded that his mother was German.

During the day, he was a good neighbor and upstanding citizen. At night, he prepared profiles for the Soviets of potential agents and wrote assessments of developing political and military situations, which he stuffed in small steal containers to be left at dead drops outside the city or in parks. He received instructions from Moscow via a shortwave radio.

He never managed to sidle up to national security advisors, but he stole computer code that helped the Soviet Union economically.

With his America persona in full swing, he vacationed yearly in East Germany for debriefings. He married his college sweetheart, Gerlinde, and started a family. It was an awkward situation because his wife was never fully aware of what he was doing in America.

In America, he was taking his double life to another level. He married a girl named Penelope, a native of Guyana, in 1985 and with her had two children, Chelsea and Jessie.

“I did a good job of separating the two” lives, he said. “Barsky had nothing to do with Dittrich and Dittrich wasn’t responsible for Barsky.”

But the facade eventually crumbled.

The collapse started in 1988 when Moscow ordered his immediate return. The KGB had information that Barsky was about to be arrested and wanted him to escape.

After 10 years of American life, he balked at the idea. He had discovered that Americans weren’t evil, as he had been told, and he had fallen for the American Dream. He stalled for a week.

After 10 years of American life, he balked at the idea. He had discovered that Americans weren’t evil, as he had been told, and he had fallen for the American Dream. He stalled for a week.

When he got the ultimatum, Barsky concocted an elaborate excuse. He knew the Soviets feared AIDS and chalked the epidemic in America up to its moral inferiority. So he told his handlers that he had contracted the HIV virus. He assured the Russians he wouldn’t defect or surrender any secrets.

Of the Soviet fears, nothing materialized. The FBI was still clueless. He eased into middle-class life in America in a comfy home in upstate New York.

Then in 1992, his cover was blown. A KGB archivist, Vasili Nikitich Mitrokhin defected and named a slew of agents to British authorities.

The FBI finally started watching Barsky to see if was an active agent.

The FBI finally started watching Barsky to see if was an active agent.

The FBI bugged his home. They purchased the house next door, and an FBI agent, Joe Reilly, posing as an ornithologist, kept him under surveillance with binoculars.

In the end, Barsky blurted out the evidence the FBI needed. In the middle of a heated argument with his wife, Barsky tried to show her how much he’d given up for her.

“I was trying to repair a marriage that was slowly falling apart,” he said. “I was trying to tell my wife the ‘sacrifice’ I had made to stay with Chelsea and her. So in the kitchen I told her, ‘By the way, this is what I did. I am a German. I used to work for the KGB and they told me to come home and I stayed here with you and it was quite dangerous for me. This is what I sacrificed.’”

Instead, she grew angrier. He had a secret life? He was in danger of being arrested?

Instead, she grew angrier. He had a secret life? He was in danger of being arrested?

Just days later, Barsky was driving home from work. When he drove out of a toll station, a Pennsylvania state trooper pulled him over. Dressed in plain clothes, Reilly asked to talk to him.

“I knew the gig was up,” he said.

Still, Barsky met the arrest with bluster: “What took you so long?”

He had gone undetected for almost 20 years – a massive embarrassment for the FBI.

For a weekend, Reilly interrogated Barsky in a motel. Bargaining for clemency, Barsky came clean with everything. Ultimately, the FBI validated his entire story and decided to let him go free. They allowed him to use the name Barsky on his now-legalized documents.

It would take more years for God to “catch” him.

It would take more years for God to “catch” him.

As a businessman, he once hired an administrative assistant who was a born-again Christian. He asked for a written composition to evaluate the effectiveness of her communication.

“She gave me an essay on the Book of Ruth,” he said. “At that point, I wasn’t an aggressive atheist anymore. I had met too many good Christians. I told (her) at the time, ‘I’m an agnostic.’ But, she sort of opened the door because once I read the essay, I said, ‘This is pretty well written.’ And out comes the Bible. She (was) a very aggressive evangelist, and she felt that there was a way to lead me to God.”

She got Barsky to listen to Ravi Zacharias, a modern C.S. Lewis. It was the first time he encountered reasonable and logical arguments for God. It also confronted him with the origin of morality.

After a second failed marriage, Barsky married a deeply Christian girl from Jamaica named Shawna. The two started attending a local church, and Barsky saw he had to come to terms with the lie he had been living.

“I had this the spiritual, emotional need that I was talking to you about, this loneliness. So she took me to her church, and the sermon was just, like, overwhelming in that the pastor mentioned the word love about 30, 40 times.”

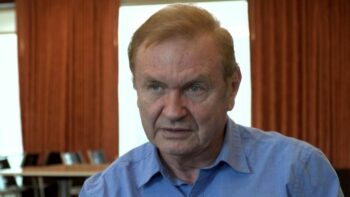

God’s love finally melted his icy heart, and Barsky was born again.

Barsky confessed the sins of his former life in front of his church and then on 60 Minutes. He wrote an autobiography, Deep Undercover.

“This kind of double life wears on you. And most people can’t handle it. I am not saying that I lived a charmed life but I got away with it,” he said. “I have had some issues with alcohol that I have overcome. And I am finally getting to live the life that I should have lived a long time ago.”

To learn more about a personal relationship with God, go here

Read about former KGB agent Sergei Kourdakov who similarly converted to Christ.

Anthony Gutierrez studies at the Lighthouse Christian Academy in West side Los Angeles.

Comments are closed.